Several years ago, I connected on Facebook with a family of Shervingtons living throughout California’s Central Valley—from Inyo County to Sacramento and Modesto. I had grown up in the San Francisco Bay Area never knowing they existed. The surname “Shervington,” along with one of its variants “Shirvington,” is rare—thankfully making genealogical research a bit more manageable than if I were tracing “Smiths” or “Joneses.”

Naturally, I tried linking this California clan to my own tree. But despite a shared surname the paper trail and DNA tests showed no known or recent common ancestry. Still, the search led me somewhere unexpected—back in time, and eventually across an ocean.

During that investigation, I traced the Central Valley Shervington family back to their immigrant ancestor, Ernest B. Shervington.1 Originally from the Greater London area, Ernest arrived in the United States in 1909 with his wife2—who was born in Luxembourg—and their three young children.3 4 5 The family initially settled in Colorado before making their way west to the San Francisco Bay Area.

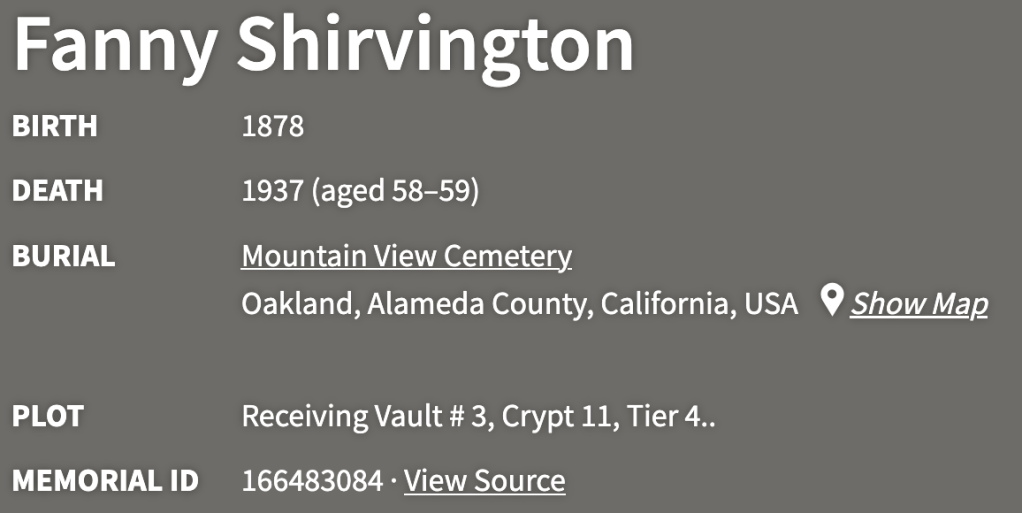

I also came across a burial listing for a Fanny Shirvington (1878–1937)6 at Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland. Since it was in the Bay Area, I assumed she belonged to the same California branch—“just another unrelated Shirvington,” I figured—and set it aside.

That is, until recently.

While researching relatives who died in military service, Fanny unexpectedly resurfaced. Not only was she connected to me by marriage—she was at the center of one of the most sensational non-military incidents I’ve ever uncovered in my family history.

A Canadian Childhood Among Scots

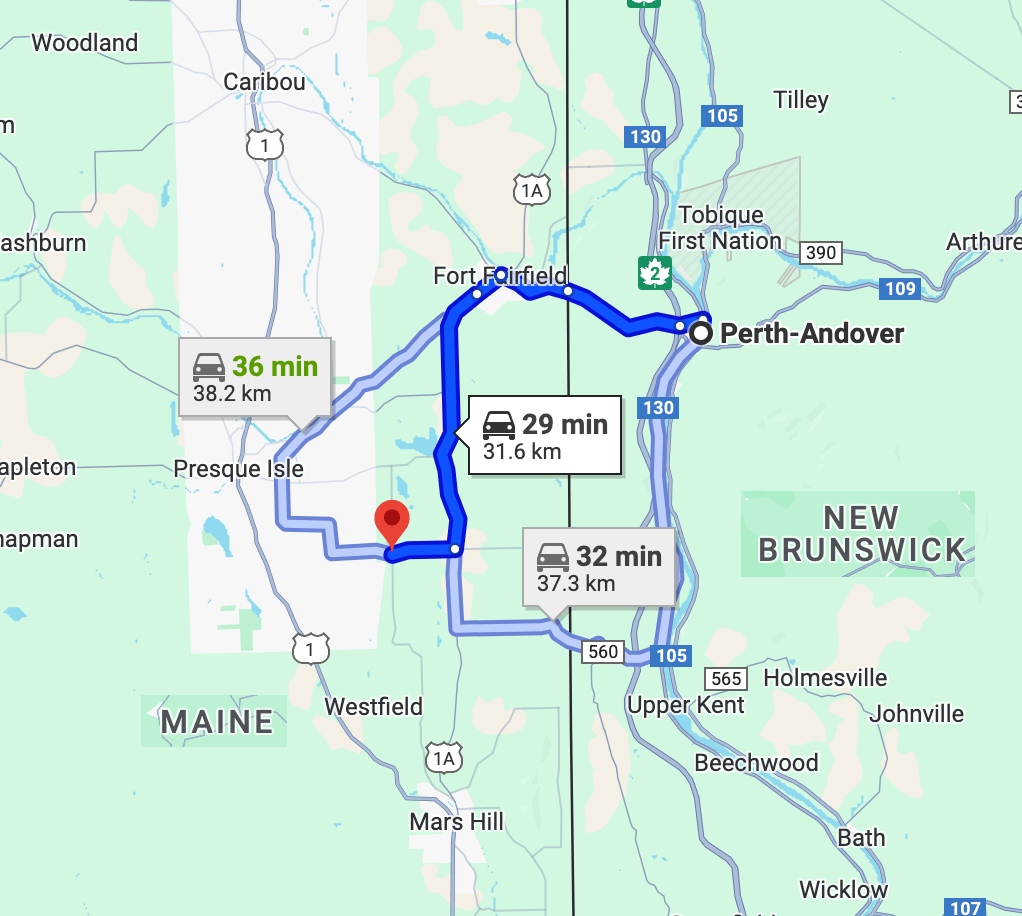

Frances “Fanny” Tompson Bruce was born in 1878 in Lower Kintore, New Brunswick—then a rural community heavily populated by Scottish immigrants. Her parents,7 8 both from Aberdeenshire, raised seven children6 9 10 11 12 13 14 on a farm. Her father eventually transitioned to railroad contracting with the Canadian railway, often working across the nearby U.S. border in Maine.

Fanny first crossed into the U.S. as a toddler in 1882 and seems to have moved frequently between Maine and Canada. By 1892, her family had settled in Easton, Maine. That same year, her father died of endocarditis, and 17-year-old Fanny married an American named John W. Fraser,15 whose father was also a Scottish immigrant. Given the prevalence of arranged marriages among Scots at the time—used to preserve language, religion, and culture—it’s possible that this was such a union.

The couple moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, but by 1900 the marriage had ended. John was living alone in a boarding house, and there’s no record of any children.

Westward Migration After the Quake

Fanny’s brother William10 married a Norwegian immigrant named Eleanor Matilda Thompson,16 who tragically died just a year later at age 24. After the devastating 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, William and two of his younger brothers—Leslie13 and Douglas14—headed west to work as carpenters during the rebuilding boom. Their widowed mother, Elizabeth,8 soon joined them.

William eventually became resident manager of the Aster House Hotel, a boarding house at 270 McAllister Street in San Francisco. Elizabeth would live there for the next two decades until her death in 1944, and William until his own death six years later.

Vanishing Act and an English Reappearance

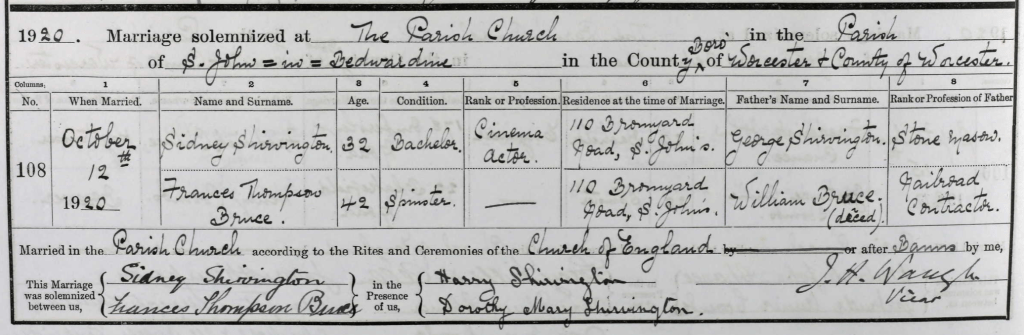

Fanny all but disappeared from the records for nearly 20 years following the collapse of her marriage. No censuses, directories, or passenger records list her whereabouts during that time—until she reemerged in Worcestershire, England in 1920, marrying Sidney Shirvington,17 my fourth cousin once removed.

Sidney was born in Worcestershire in 1878 and served with the 2nd Battalion of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. By 1911, he had attained the rank of lance corporal, with overseas postings in Mauritius and later in Hong Kong. His military records show no service in active combat, indicating that he likely left the army before his unit departed China for the Western Front in 1914. After his discharge, Sidney may have chosen to remain in China, making it his home for a time. This would have been a logical choice, as both the fully autonomous British colony of Hong Kong and the port city of Shanghai—with its foreign-controlled concessions—offered significant opportunities for colonial expatriates, investors, and workers during that era.

At some point, Sidney chose to settle in Canada, as he reappears in the records in October 1919, departing Quebec aboard the Empress of France. He listed his occupation as “warden” and identified Canada as his permanent residence.

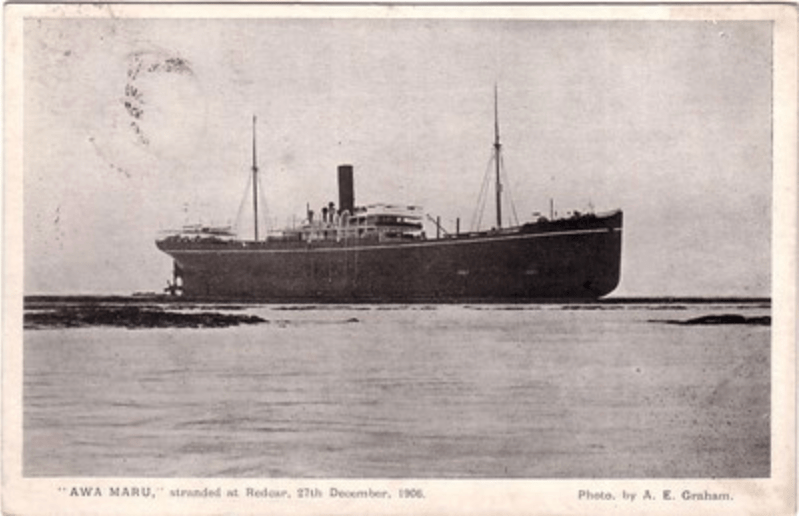

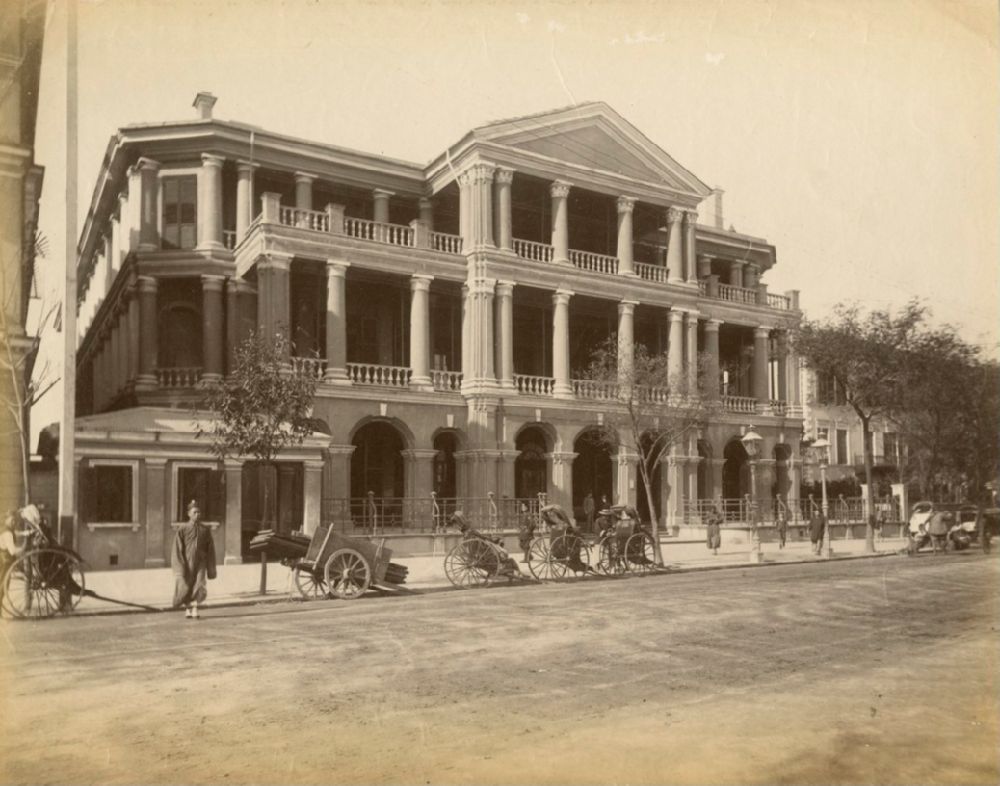

After a 20-year gap in her records, Fanny suddenly reemerges on October 12, 1920—in England. She and Sidney registered their marriage at St. John’s Baptist Church in Bedwardine, Worcestershire. How their lives intersected remains a mystery. Curiously, Sidney listed his occupation as “cinema actor,” which may have reflected a hopeful ambition rather than an established career. Just a few months later, in March 1921, the newlyweds boarded the steamship Awa Maru, bound for Shanghai, China. They will live in a room at the world renowned, Shanghai Club.

Life in the Shanghai Club

About the Shanghai Club

The Shanghai Club was the most exclusive gentlemen’s club in Shanghai during the colonial period, situated on the Bund at No. 2. Founded in 1861, the club catered primarily to wealthy British expatriates and was renowned for its strict membership policies—no women allowed, no Chinese members, and a dress code that mirrored British aristocratic standards. Its Long Bar, stretching 110 feet, was the longest in the world at the time. The club served as a hub of colonial power, social networking, and deal-making in an era when Shanghai was considered the “Paris of the East.”

Fanny and Sidney settled into this world of opulence. Sidney first found work as an assistant inspector with the Public Works Department while Fanny was listed as a housewife. But by 1927, she was employed as a matron, a supervisory role likely overseeing domestic staff within the club.

Records show she frequently returned to San Francisco to visit her family, staying for several months at a time at the Aster House with her mother and brother, William. She never became an American citizen, instead traveling on a British passport.

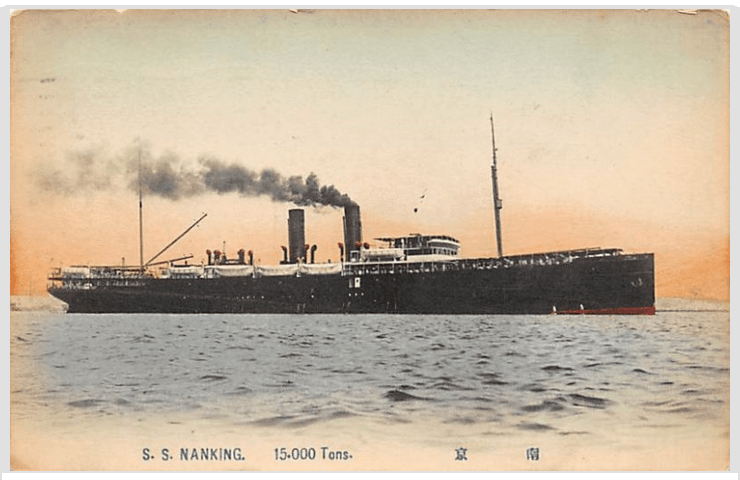

1923- Fanny takes the S.S. Nanking to San Francsico.

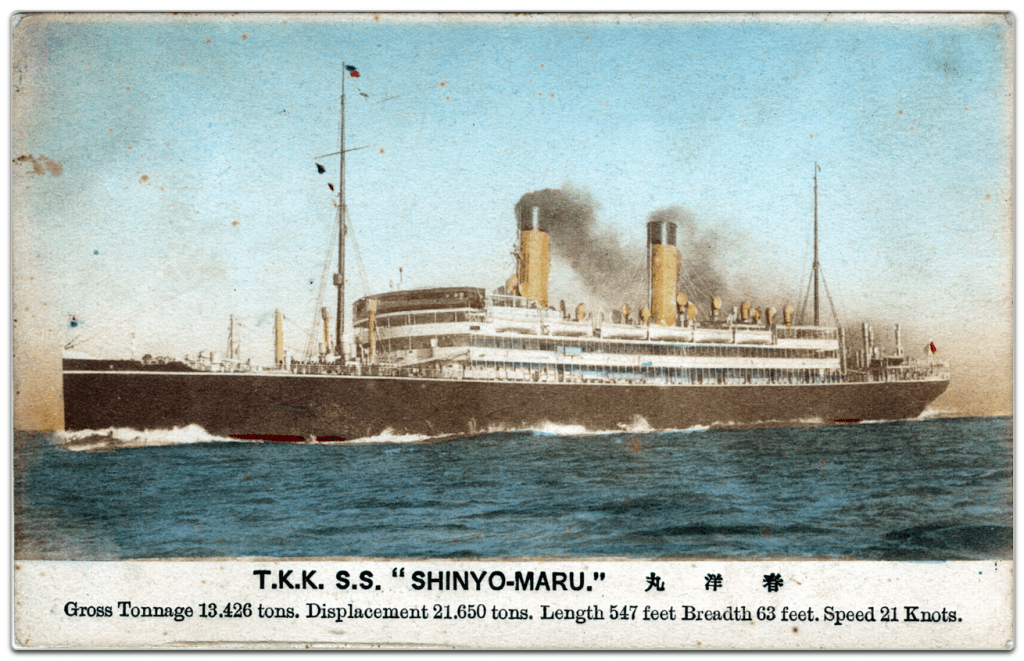

1927 – Fanny boards the S.S. Shinyo Maru for California.

1929 – Fanny takes the S.S. Taiyo Maru to San Francisco.

Sidney transitioned from his public works job to serving as a warden—likely with the prison system or local constabulary—before becoming a caterer and steward at the Shanghai Club itself by 1928. The couple lived on-site, both in supervisory roles typical of expatriate couples of the time.

In May 1928, Sidney traveled to London to attend his niece Dorothy’s20 wedding. It was to be his final journey home.

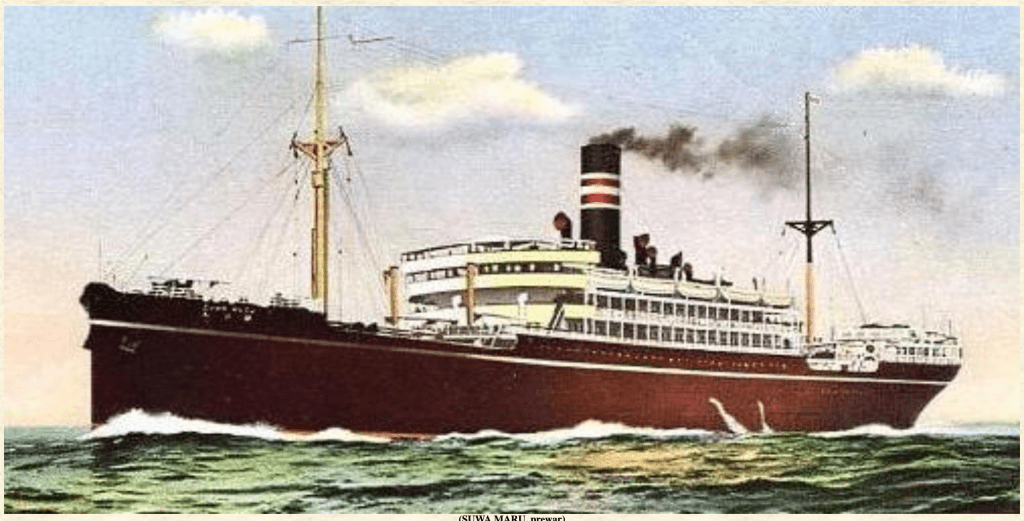

1928 – Sidney boards the S.S. Suwa Maru bound for London with stops in Singapore, Penang, Naples, Marseilles, and Gibraltar. The Suwa Maru will be sunk by the U.S.S. Tunny in 1943 of the coast of Wake Island.

Murder—or Madness?

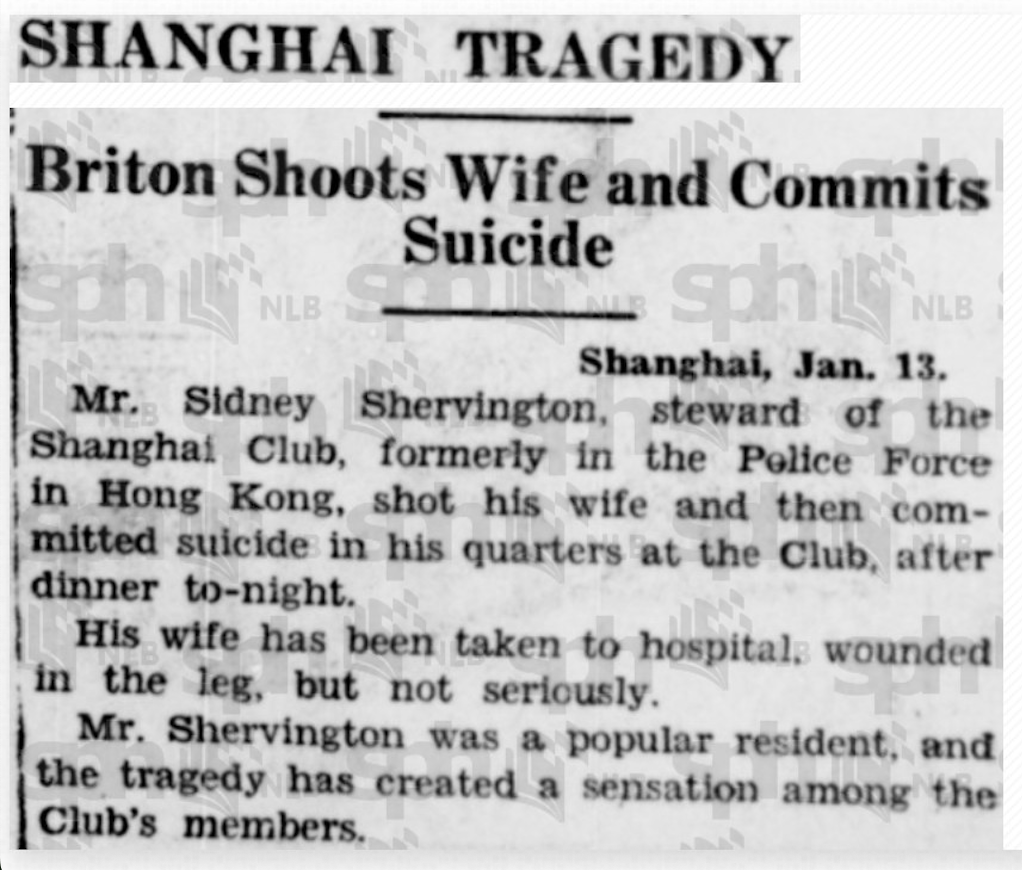

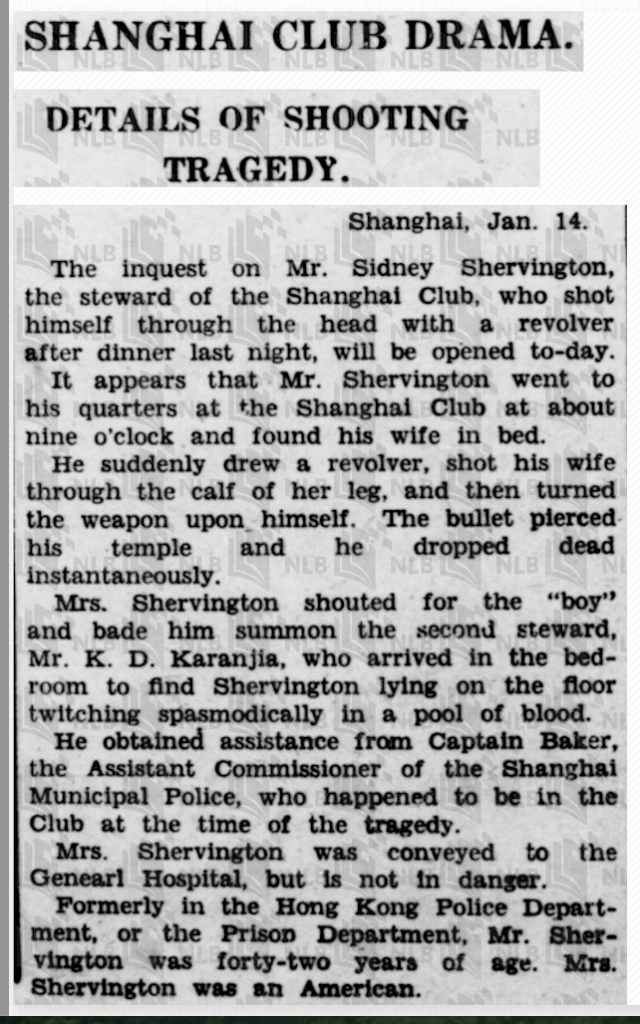

On January 21, 1932, tragedy struck.

According to official accounts, Sidney returned to their apartment in the Shanghai Club after dinner and, while Fanny lay in bed, shot her in the leg—then turned the gun on himself. Fanny, wounded, screamed for help. A steward and an assistant police commissioner who happened to be dining in the club rushed in. They found Sidney still alive, twitching, and moments later, dead.

Apparently an inquest declared it act of attempted murder-suicide, and the case was closed as no arrest was made, and Fanny continued to work at the Shanghai Club for more than two years after the incident.

But among Sidney’s British relatives, the whispers never stopped. Many believed Fanny had gotten away with murder. Two shots were fired, but with only the two of them in the room, no one could say for certain who held the gun or pulled the trigger. Questions lingered: why was Fanny only shot in the leg? If Sidney had been the one to fire, how could he have missed a more fatal area—especially in such a small room, with Fanny lying defenseless in bed? And if it was truly meant to be a murder-suicide, why just one shot? Why didn’t he fire multiple rounds out of anger and save the last for himself?

Frustratingly, the inquest records appear to have never been released—perhaps not surprising in an era when colonial authority was tightly held by the elite. Inquests at the time could be quietly shaped by power, wealth, and political convenience.

Return to San Francisco

S.S. Asama Maru ca. 1930. Sunk in 1943 by the U.S.S. Atule while operating as a Japanese troop ship in the South China Sea.

Nine months later, in November 1932, Fanny returned to San Francisco aboard the Asama Maru. She was still listed as a matron and traveling on her British passport. In 1934, she again boarded the Taiyo Maru, this time declaring her intention to settle permanently in California.

She returned to the Aster House Hotel, where she lived with her aging mother and brother, William. Just under three years later, Frances “Fanny” Tompson Bruce Shirvington died at the age of 58.

Legacy in Silence

Fanny’s story spans continents—Scotland, Canada, Maine, Massachusetts, England, Shanghai, and finally San Francisco. Her life was shaped by war, loss, reinvention, and a dramatic ending during the Great Depression that still leaves lingering questions. She was a housewife. A matron. A traveler. Perhaps a survivor—or perhaps a murderer.

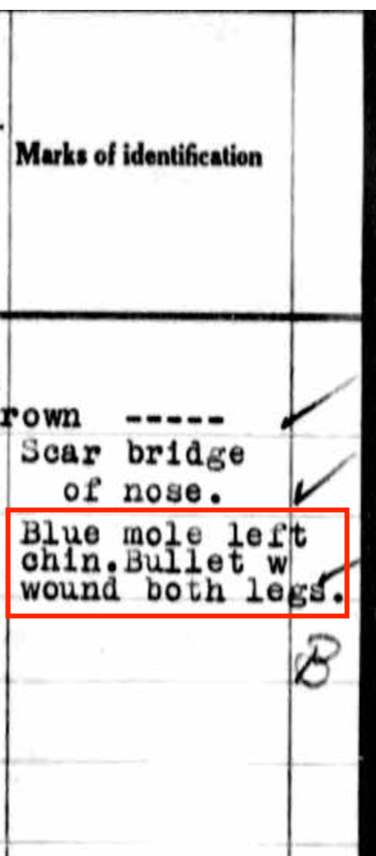

Her ocean crossings serve as more than mere chapters in her life; they hold clues. I’ve highlighted those voyages here for a reason. One passenger manifest, in particular, hints at something that might sway belief in her innocence. On her final recorded journey in 1934, Fanny listed her “marks of identification” as a blue mole on her chin—and bullet wound scars in both legs. That detail matters. After all, it’s both rare and physically difficult to shoot oneself in both legs.

And then there’s Sidney. A veteran with the capacity to lead and adapt, he took charge of his own fate, following opportunity wherever it led—even across oceans. He married at 32—late for the time—and built a life far from home. Perhaps he struggled with depression. Perhaps the crushing weight of the Great Depression, felt around the world, became too much for him to bear.

The only certainty is this: their stories deserve to be remembered.

- Ernest B. Shervington (1880-1943), Find A Grave ID: 137771586; Wikitree ID: Shervington-43 ↩︎

- Catherine Maria Florence (Irthum) Shervington (1880-1963), wife of Ernest B. Shervington. Find A Grave ID: 137771587; Wikitree ID: Irthum-54 ↩︎

- Kathleen Amy (Shervington) Field (1902-1996), daughter of Ernest and Katherine Shervington. Find A Grave ID: 291403110; Wikitree ID: Shervington-44 ↩︎

- John Ernest Shervington (1904-1998), son of Ernest and Katherine Shervington. Find A Grave ID: 263230224; Wikitree ID: Shervington-45 ↩︎

- Charles Arthur Shervington (1906-1972), son of Ernest and Katherine Shervington. Find A Grave ID: 15451553; Wikitree ID: Shervington-46 ↩︎

- Frances “Fanny” Tompson (Bruce) Shirvington (5 Jun 1878), wife of Sidney Shirvington. Find A Grave ID: 166483084; Wikitree ID: Bruce-15254 ↩︎

- William Bruce (1854-1892), Father of Fanny. Find A Grave ID: 184543465; Wikitree ID: Bruce-15255 ↩︎

- Elizabeth (Malcolm) Bruce (1854-1944), mother of Fanny. Find A Grave ID: 166483123; Wikitree ID: Malcolm-3348 ↩︎

- Lillian Tompson Bruce (1876-1900), daughter of William and Elizabeth Bruce. Find A Grave ID: 184543579; Wikitree ID: Bruce-15256 ↩︎

- William Bruce (1876-1950), son of William and Elizabeth Bruce. Find A Grave ID: 166483106; Wikitree ID: Bruce-15257 ↩︎

- George Malcolm Bruce (1878-1938), son of William and Elizabeth Bruce. Find A Grave ID: 249231926; Wikitree ID: Bruce-15258 ↩︎

- Barnett Henry Bruce (1882-1920), son of William and Elizabeth Bruce. Find A Grave ID: 184543560; Wikitree ID: Bruce-15259 ↩︎

- Leslie Mavor Bruce (1884-1969), son of William and Elizabeth Bruce. Find A Grave ID: 87573815; Wikitree ID: Bruce-15260 ↩︎

- Douglas Lawson Bruce (1887-1987), son of William and Elizabeth Bruce. Find A Grave ID: 166831681; Wikitree ID: Bruce-15261 ↩︎

- John Wilson Fraser (1876-1945), 1st husband of Fanny Bruce. Find A Grave ID: 177389032; Wikitree ID: Fraser-16927 ↩︎

- Eleador Matilda Thompson (1876-1900), wife of William Bruce. Find A Grave ID: 264613760; Wikitree ID: Thompson-105231 ↩︎

- Sidney Shirvington (1888-1932), 2nd husband of Fanny Bruce and 4th cousin once removed of the author. Find A Grave ID: 291403875; Wikitree ID: Shervington-39 ↩︎

- Harry Shirvington (1899-1977), younger brother of Sidney Shirvington. Find A Grave ID: 291404133; Wikitree ID: Shervington-40 ↩︎

- Dorothy Mary Shirvington (1902-1993), niece of Sidney Shirvington. Find A Grave ID: 291416710; Wikitree ID: Shervington-42 ↩︎

One thought on “Gunfire at the Shanghai Club: The Untold Story of Fanny Bruce and Sidney Shirvington”