While researching my family history, I was deeply moved to learn that several of my distant relatives lost their lives in various wars. Discovering their stories and the sacrifices they made gave me a profound sense of connection to the past and a greater appreciation for the freedoms I have today. It’s humbling to recognize the personal cost of conflict and to see how courage and loss are a part of our own family’s legacy. These are their stories.

World War II

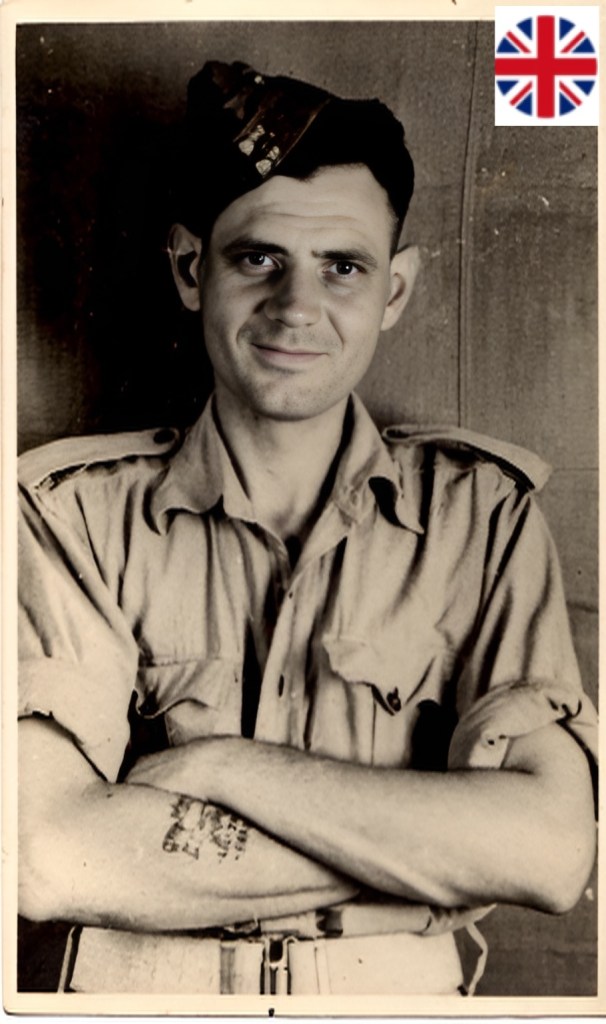

John “Jack” Shervington1

Gunner

Royal Army

113th Royal Field Artillery Regiment / 56th (London) Division

Killed in action January 28, 1944

Italy

27 years old

1938 – Marriage and War

In 1938, Jack—his preferred name—married Lily.2 Just over a year later, World War II erupted. Lily’s father,3 a merchant marine, had been killed in World War I when she was just two years old. His requisitioned trawler hit a mine during a German U-boat attack on a convoy he was leading. With the onset of another global conflict so close to their wedding, and with Jack’s decision to enlist in the Royal Army, it’s perhaps not surprising that by 1941, the couple had yet to start a family.

1941 – Three Brothers, Two World Wars

Jack, along with his brothers Alfred4 and Frederick,5 all from Exeter, England, served in the defense of Europe. Alfred, the eldest, fought in World War I and returned home after recovering from a mustard gas injury sustained in the trenches of France. Fred, the youngest at 20, enlisted with Jack to fight in World War II. Whether by chance or by the needs of the Royal Army, Jack and Fred were assigned to separate field artillery units—both of which would soon see action.

1941–1943 – First Contact

Jack served as a gunner with the 113th Field Artillery Regiment of the 56th (London) Division. His first combat deployment came in November 1942, when a pro-Nazi coup overthrew the British-allied regime in Iraq. Meeting little resistance, Jack and his division continued through Palestine and Egypt, eventually arriving in Libya by April 1943—completing a remarkable 2,300-mile mechanized march.

It was in Tunisia that the 56th faced their fiercest test yet. Confronting Germany’s battle-hardened 90th Light Infantry Division, the regiment endured heavy losses. Despite the challenges, their efforts contributed to the broader Allied campaign, linking up with forces that had landed as part of Operation Torch.

Italy, 1944 – One Brother Falls

While the 56th (London) Division sat out the Battle of Sicily in August 1943, they were called back into action early the following year. On January 22, 1944, Jack and his regiment landed at Anzio, Italy, as part of Operation Shingle. The mission aimed to break the stalemate at the Gustav Line and open the road to Rome.

The landing was initially successful, but the advance quickly stalled in the face of fierce German resistance. Tragically, Jack was killed in action just six days later, on January 28. The beachhead would remain contested for months, but Jack’s comrades pushed on. By June 1944, the Allies had finally broken through and liberated Rome—a victory Jack never lived to see, but one he helped make possible.

A Brother’s Legacy

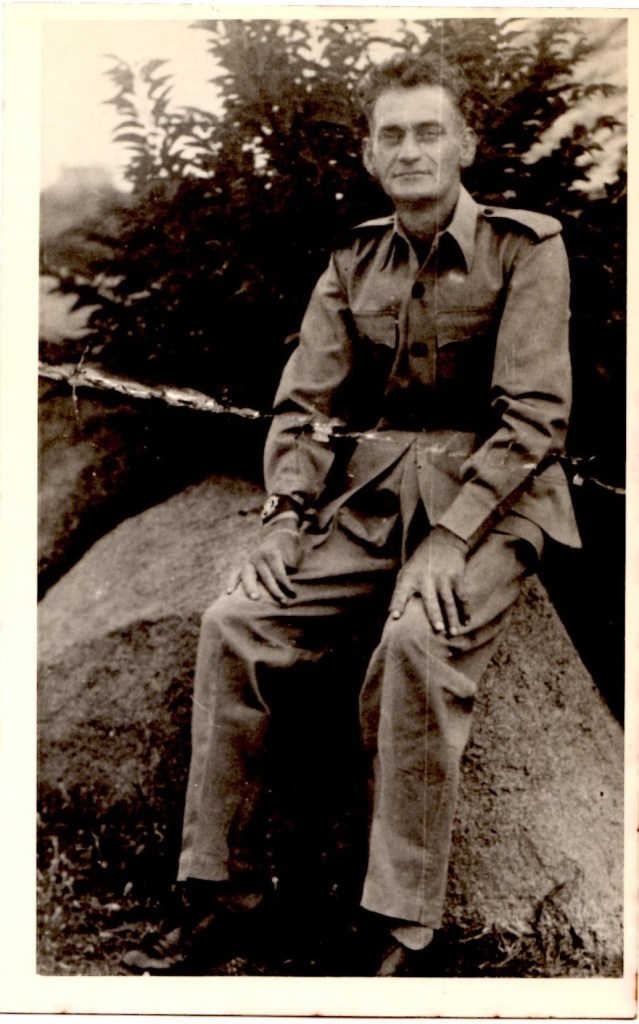

Jack’s younger brother, Frederick, served as a signaler with the Ayrshire Yeomanry, 152nd Field Artillery Regiment. Like Jack, he fought in North Africa during the same period, and arrived in Italy just two months after his brother’s death.

Frederick continued the fight through the grueling Italian campaign, serving with distinction in key battles at Monte Grande, Perugia, and Arezzo. At Monte Penzola, he was awarded a commendation for bravery under fire. Jack would undoubtedly have been proud of his brother’s courage and resilience amid the unrelenting hardships of war—and could rest in peace knowing that Frederick made it home.

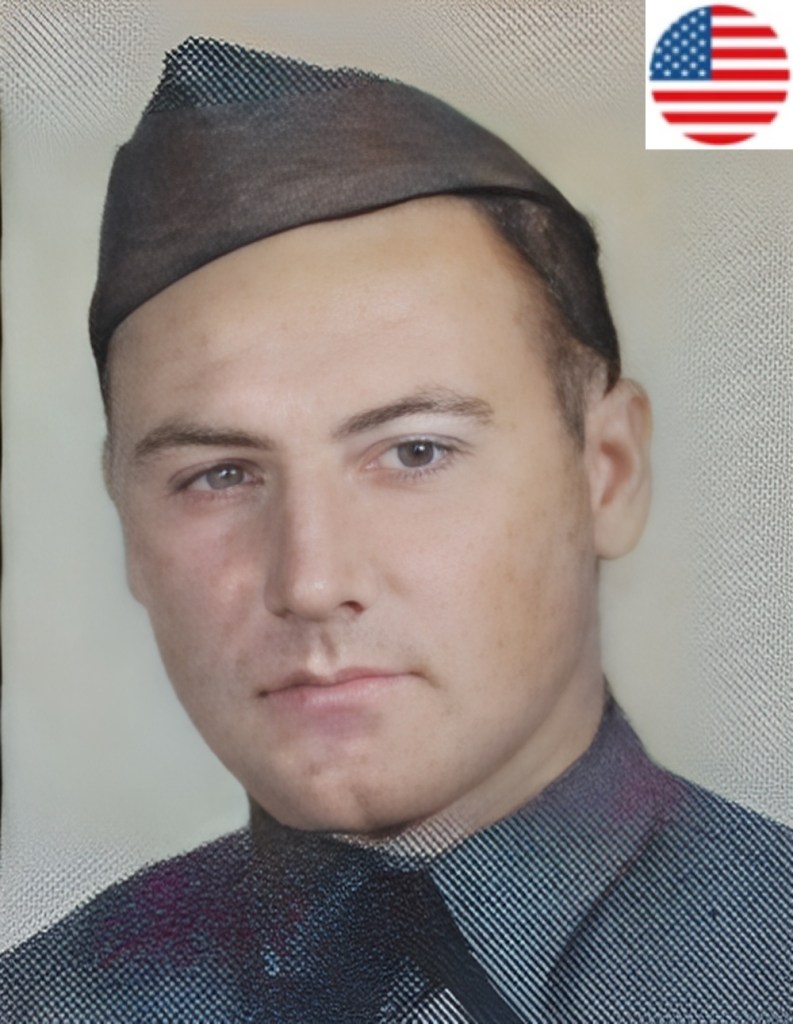

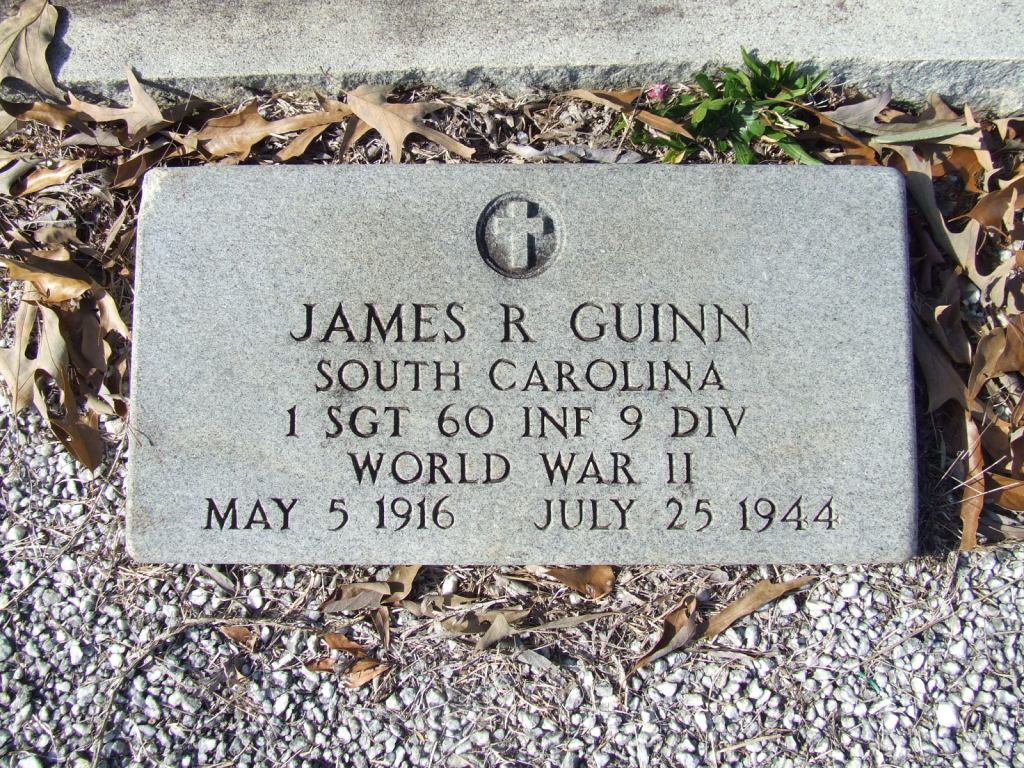

James Ralph Guinn6

First Sergeant

U.S. Army

60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division

Killed in action July 25, 1944

France

28 years old

1940 – Pre-WWII South Carolina

In 1940, with the world edging closer to full-scale war, my 3rd cousin, James volunteered for military service. His decision may have been influenced by the growing sense across the nation that U.S. involvement was inevitable. Overseas, Hungary, Slovakia, and Romania had aligned themselves with the Axis powers, while closer to home, the German Navy posed a looming threat along the eastern seaboard—including the coastal waters of South Carolina.

1941–1943 – We’re in the Fight

Following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s official entry into World War II, James was already well-prepared, having spent nearly two years in military training. Serving with the 60th Infantry Regiment, he saw his first combat during Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942. The campaign marked a critical early victory—ports and kasbahs were captured, and by April 1943, a significant counterattack by Vichy French and German forces had been successfully repelled.

1943–1944 – Another Beach Landing

Now a battle-hardened soldier, James and the 60th were deployed to the shores of Sicily as part of the Allied push into Europe. Landing at Palermo in August 1943, their mission was to outflank entrenched enemy artillery protecting Axis front-line troops. Just as they had done in North Africa, the 60th cleared the path for Allied advances, steadily forcing German and Italian forces to retreat. After seven months of grueling combat, the island was under full Allied control by November 1943.

June 1944 – A Leader Emerges and Falls

With two major campaigns behind him, James had risen to the rank of First Sergeant, leading as many as 200 men. He and his regiment were sent to England for a brief rest and intensive training, unaware they would soon take part in the largest amphibious assault in history. While the 60th was held in reserve during the initial D-Day landings—perhaps in recognition of their proven effectiveness in urban battles—they were called upon shortly after to lead the push inland.

Four days after the beaches of Normandy were secured, James and the 60th Infantry Regiment landed and began driving the Germans back. On June 26, they helped liberate the strategic port city of Cherbourg. Unfortunately, just a month later, on July 25, James was killed in action during the unit’s advance toward Belgium. The town of Momignies—the first in Belgium to be liberated—would fall to the Allies six weeks later, on September 2, 1944.

Ernest Walter Pimm7

Seaman

Royal Navy

Royal Navy Patrol Service HMPV Danehill

Died December 2, 1941

England

28 years old

1939 A Baker’s Salesman – Just prior to the start of WWII, Ernest was 26 years old, single and working as a salesman for a bakery in Birmingham, West Midlands, UK. He was the only son of Walter Pimm8 and my 3rd cousin, Beatrice Shervington.9 He had two younger sisters Edith and Rose. Sometime after the hostilities began, Ernest joins the Royal Navy Patrol Service helping to fill a vital role in protecting the British mainland from German sea attacks and safeguarding coastal shipping routes.

December 1941 – The United Kingdom and its European allies were entering their third year of war as German troops closed in on the outskirts of Moscow. Meanwhile, the United States remained on the sidelines, seemingly indifferent to the atrocities unfolding across the Atlantic. But that was about to change.

On December 2nd, Japanese Rear Admiral Matome Ugaki10 received orders to proceed with the attack on Pearl Harbor. That same day, Seaman Ernest Pimm was serving aboard Her Majesty’s Patrol Vessel (HMPV) Danehill.

HMPV Danehill had docked at a refueling depot, HMS Calliope, located in North Shields on the River Tyne, just before it flows into the North Sea. Tragically, a sudden fuel explosion rocked the depot as they took on petrol. Ernest was gravely injured and died later that day at the Jubilee Infirmary.

Ernest would never witness the shift in the tide of war—just five days later, the United States would enter the conflict, bringing with it a surge of hope and renewed determination for the Allied cause.

David Adams Nye11

1st Lieutenant

U.S. Army Air Force

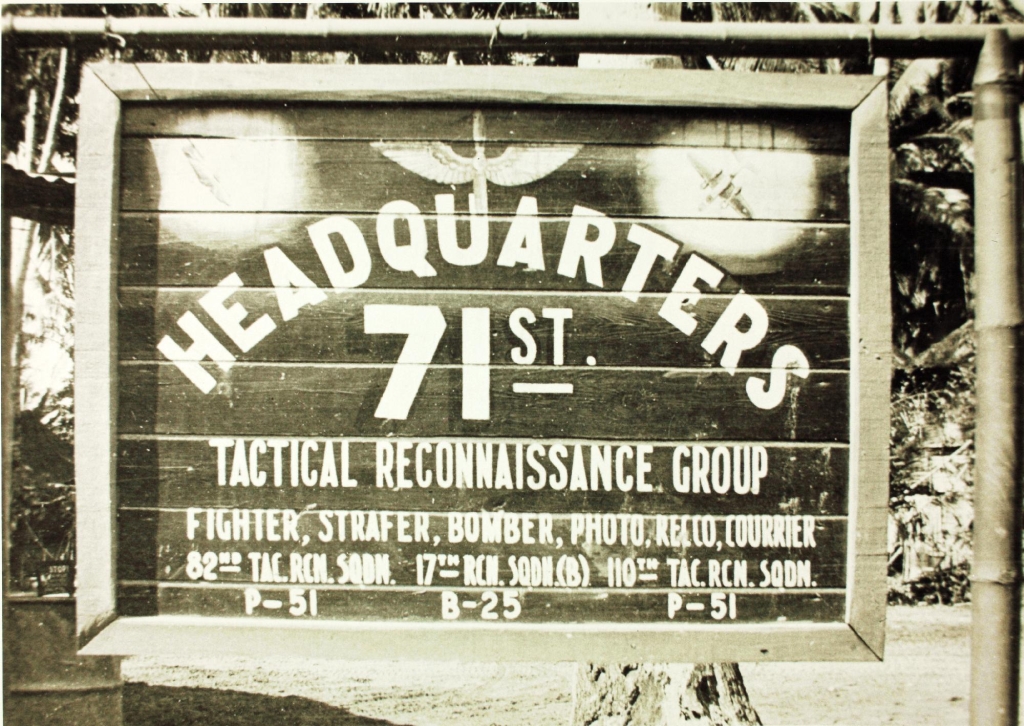

71st Tactical Reconnaissance Group

Missing in Action June 1, 1945

Formosa (Taiwan)

24 years old

A 1635 Grandfather

David was born in 1921 in Swampscott, Massachusetts, the only son in his family,12 13with one younger sister.14 He and I are 5th cousins, connected through our several-times great-grandfather, Benjamin Nye,15 who emigrated from Kent, England to the American colonies sometime before 1635—roughly fifteen years after the Mayflower’s arrival.

A Pre-War Student

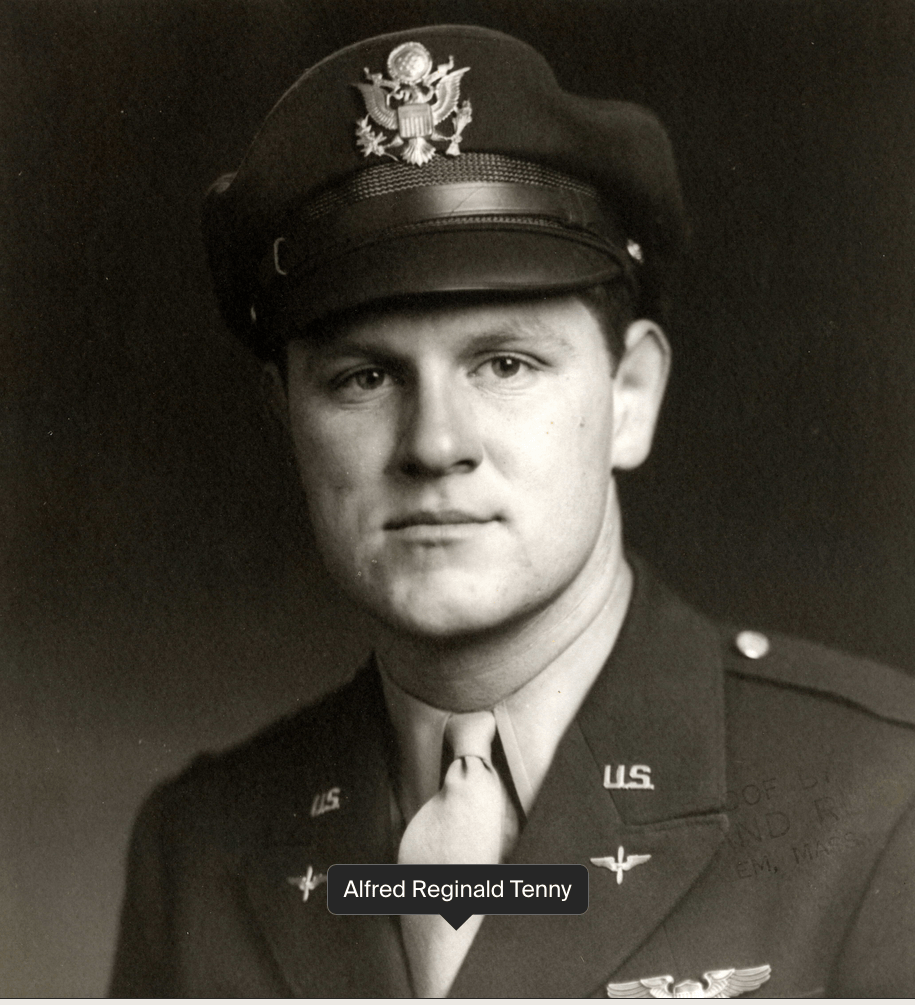

David graduated from Marblehead High School in 1939. Along with his neighborhood friend and classmate, Alfred Tenny Jr.,16 he was accepted to Worcester Polytechnic Institute, where both became members of the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity. In 1941, David also participated in a program at the General Electric Apprentice School. However, like many young men after the attack on Pearl Harbor, David chose to serve his country and enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force as an aviation cadet. His friend Alfred joined as well.

Commissioned Officers

Continuing their journey together as they had in high school and college, David and Alfred attended Army Air Forces cadet school in Selma, Alabama. Both earned their commissions as second lieutenants and, after several additional months of solo flight training, were promoted to first lieutenant. They were each assigned to tactical reconnaissance units—critical roles that involved gathering both real-time and photographic intelligence on enemy positions, troop movements, and target locations. In addition to reconnaissance, their missions often included providing air support for bombers and ground forces, as well as offering tactical guidance based on their aerial observations.

Divergent Flight Paths – In 1943, both pilots trained to to fly single engine aircraft are assigned to different theaters of war. David is sent to the pacific with the 71st Tactical Reconnaissance Group (71st TRG) and at first is flying missions out of New Guinea. Alfred goes to Europe with the 10th Tactical Reconnaissance Group (10th TRG) and flies his missions out the RAF Chalgrove Airfield in Oxfordshire, England.

A Friend Falls

Following the Allied breakthroughs in France and Belgium after the 1944 Normandy invasion, Alfred and the 10th TRG relocated from England to forward airfields in France. On December 16, 1944, German forces launched a fierce counteroffensive through the Ardennes region—marking the start of the Battle of the Bulge. Just days later, on Christmas Eve, David’s childhood friend Alfred was flying a reconnaissance mission in his P-51 Mustang somewhere over Belgium when he was reported lost.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Formosa Air Battle

In October 1944, David and the 71st TRG joined Allied forces in a series of sustained air assaults on Japanese positions across Formosa—modern-day Taiwan. These strikes were part of a larger strategy to cripple Japanese air power and sever supply lines ahead of the campaign to liberate the Philippines, which would culminate in the pivotal Battle of Leyte Gulf.

A Final Flight

By February 1945, David was flying reconnaissance missions with the 71st TRG from the recently recaptured Binmaley Airstrip on Luzon, providing crucial intelligence and support for Allied operations across the region. At the time, Allied planners had considered launching a ground invasion of Japanese-held Formosa as part of their broader strategy to gain control of the Philippine Sea. However, by June 1945, military leaders determined it was more strategic to concentrate ground forces on the Philippines and other Pacific islands in preparation for a possible invasion of Japan’s home islands.

Note: Incredibly, I came across this photo among a collection dated May 1945. Although no names were provided, I believe the pilot seated in the bottom row, fifth from the left, bears an uncanny resemblance to David. If this identification is correct, the photo was taken less than a month before his disappearance.

Instead of a full-scale invasion, Formosa was kept under pressure through relentless bombing raids and fighter strikes. Whenever the Japanese attempted to repair airfields or infrastructure, Allied forces would destroy them again before they could become operational. It was during one of these missions—on June 1, 1945—that David was dispatched to support a B-29 bombing operation. Tragically, this would be his final flight. He was reported missing in action and later declared unrecoverable.

World War I – The Great War

Charles Henry Shirvington17

Private

Royal Army

95th Company of the Royal Machine Gun Corps

Killed in Action May 7, 1917

France

19 years old

July 1914 – Volunteers to Fight At just 16 years old, Charles stepped forward to volunteer for military service, joining his two older brothers18 19 in the wake of World War I’s outbreak. He was one of an estimated 250,000 underage teenagers who enlisted during the Great War.

Only two years had passed since the brothers lost their father20 at age 47. Their decision to enlist may have stemmed from a blend of patriotism and a desire to lighten the load on their widowed mother21 and only sister.22 Whatever their reasons, one thing is clear: the bond between the brothers was unbreakable—strong enough to carry them into the ranks of the Royal Army, side by side.

May 1916 – On the Western Front

By May 1916, as the war entered its third year, Charles—now 18—arrived in France with the 95th Company of the Machine Gun Corps. Had he not volunteered, he would have faced conscription by this point. His youth may have delayed his deployment to the front, but the time had come. Over the next year, Charles would serve on the Western Front, participating in the grueling First Battle of the Somme as Allied forces pushed eastward.

Despite the harsh conditions of trench warfare, mail continued to reach the troops with remarkable regularity. It’s likely Charles had already received word from home—news that his brother George was still alive, enduring his second year as a prisoner of war in a German camp. Meanwhile, his other brother, John, remained stationed in England with the Territorial Forces, continuing to defend the home front.

April 1917 – Orders to Advance

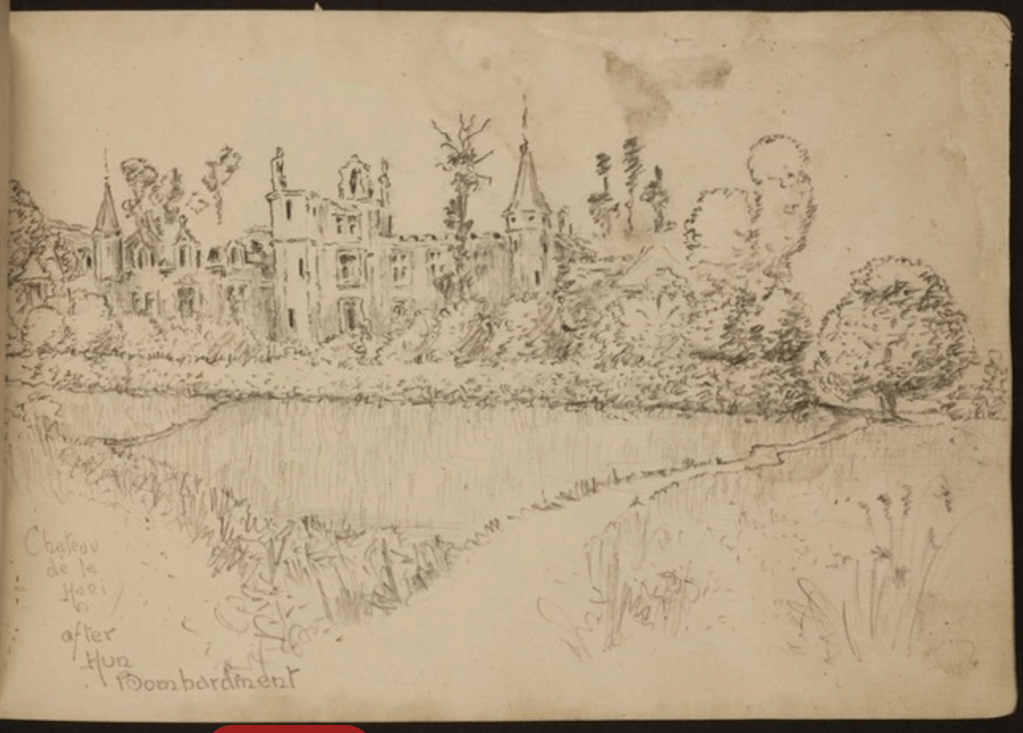

All front-line units receive orders to move forward, signaling the beginning of the Second Battle of Arras. Charles has now spent a full year in relentless combat, advancing from trench to trench and drawing ever closer to Belgium. As German forces retreat, they destroy infrastructure to hinder the Allied advance. Charles’s unit eventually takes shelter in the Château de la Haie, recently vacated and damaged by the withdrawing enemy.

May 1917 – A Soldier Falls

The British offensive at Arras results in the most significant advance since the start of the war. After four weeks of hard-fought progress, German resistance begins to stiffen. Reports of enemy shelling, sniper activity, and troop movements become more frequent. Just nine days before the battle settles into another stalemate and both sides return to trench warfare, Charles is struck by a bullet that wounds his head, eye, and ear. He is transported by field ambulance to a casualty collection station, where he succumbs to his injuries.

Tragically, Charles would never know that his brother John would suffer a duty-related accident only four months later, resulting in a brain injury that ended his military service. Nor would he see his brother George make it home safely after enduring captivity in a German POW camp until the war’s end.

Thomas. H. Shirvington23

Private

Royal Army

London Regiment, Prince of Wales Own Civil Service Rifles

Killed in Action September 29, 1918

France

22 years old

Pre-War Deployment

Thomas—a first cousin of Charles,17 mentioned earlier—turned 18 in June 1914—just one month before the outbreak of World War I. He enlisted in the Prince of Wales’s Own Civil Service Rifles, a proud, all-volunteer rifle regiment based out of Somerset House. Though originally slated for overseas deployment, those plans were postponed in April 1916 when the unit was redirected to Ireland to help maintain order during the Easter Rebellion.

June 1916 – First Battle of the Somme

Thomas entered combat on the Western Front in June 1916, just three months after the death of his mother24 at age 44. Unmarried and still grieving, he joined the fight as tensions escalated. A month later, the First Battle of the Somme began. After nearly five months of brutal trench warfare and staggering casualties on both sides, the Allies failed to break through the German lines. The battle ended in a costly stalemate.

November 1916 – Macedonian Front

With the Western Front deadlocked, Thomas and his unit were redeployed to Salonika in November 1916 to bolster Serbian forces under siege from Bulgaria, Austria-Hungary, and Germany. After over a year of promises, the Allies were finally delivering reinforcements. Thomas’s unit took part in the Battle of Doiran, a costly engagement that saw 12,000 British casualties for a modest 25-mile advance. In contrast, Bulgarian forces reported only 2,000 losses. Once again—just as in the Somme—Thomas found himself locked in a grueling stalemate, trading lives for inches.

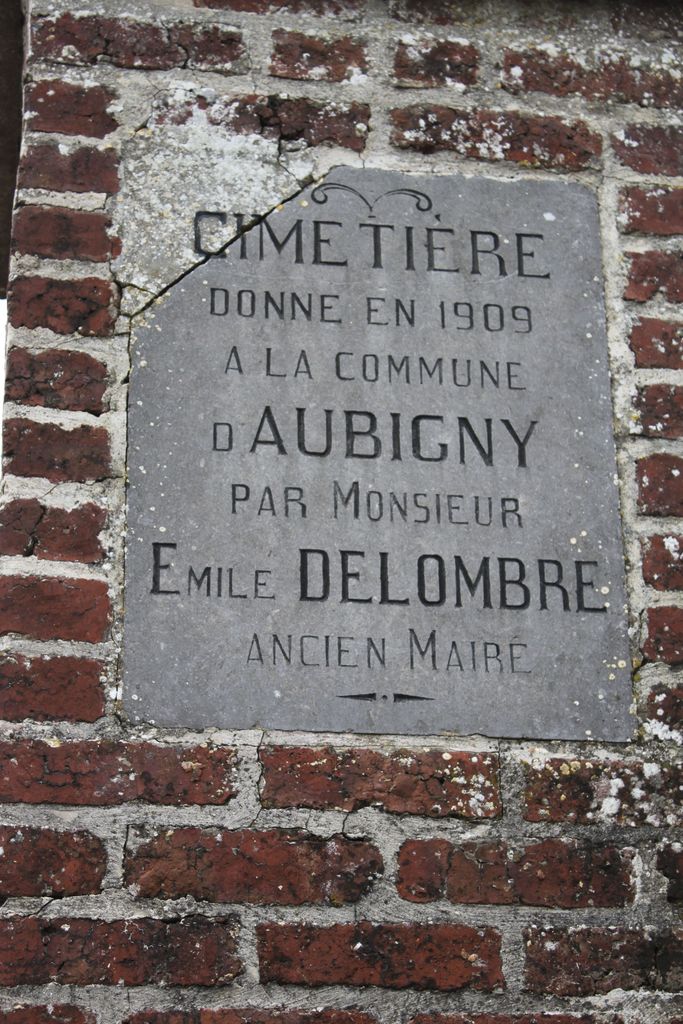

June 1917 – North Africa to the Middle East

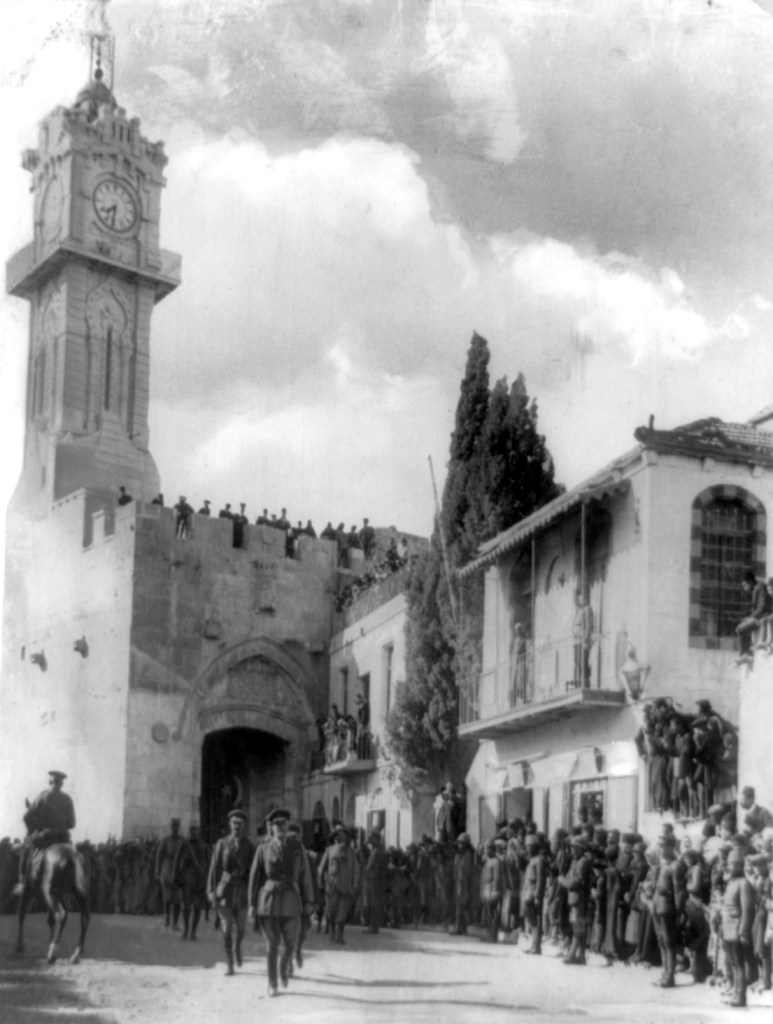

After seven grueling months on the Macedonian Front, Thomas and the Prince of Wales’s Own Civil Service Rifles joined the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. They were stationed at the Moascar Isolation Camp near the Suez Canal for rest, recovery, and renewed training. But the respite was brief—soon, they were back in action, pushing northward from the southern Suez Canal Zone into Palestine.

At last, the tide seemed to turn. Beginning with the Third Battle of Gaza, the regiment saw a string of victories, capturing key Ottoman command positions and playing a role in the liberation of Jerusalem. Yet the momentum didn’t last. In the harsh terrain east of the Jordan River, during the Second Battle of Jordan, they encountered fierce resistance and were ultimately forced to retreat.

June 1918 – Back to the Somme Valley

After a year away from the European mainland, Thomas—likely weary from years of fighting—returned to the familiar, war-torn trenches of the Western Front in France. In his absence, the Germans had launched a series of aggressive and initially successful offensives during the Spring of 1918, pushing Allied forces back across key positions. In response, the Allies prepared a massive counter-offensive, reinforcing the front lines with fresh troops. Thomas’s rifle company was among those sent back into the fray, once again facing the brutal realities of trench warfare in the Somme.

September 1918 – Luck Runs Out

As the Allies pressed forward in the final phase of the war—the Hundred Days Offensive—victories were mounting across the Western Front. Thomas was engaged in the Fifth Battle of Ypres, a key push in this final campaign. But just as the end seemed near, his luck ran out. On September 29, 1918, less than two weeks before the armistice was signed, Thomas was killed in action—so close to peace, yet never to see it.

George Ernest Barber25

Private

Royal Army

48th Machine Gun Company

Missing in Action September 7, 1916

France or Belgium

23 years old

1915 – A Gardener Trades His Hoe for a Machine Gun

George, the only son of George Samuel Barber26 and Mary Elizabeth Shervington,27 lived in Coleshill, Warwickshire, surrounded by his five sisters.28 29 30 31 32 At 22 years old, unmarried and working as a gardener at a local nursery, he exchanged his peaceful tools for the weapons of war—enlisting in the Royal Army as the Great War continued to escalate.

June 1916 – First Battle of the Somme

Following in the footsteps of his cousins Thomas17 and Charles,23 George arrived in France to take part in the First Battle of the Somme. Serving with the 48th Machine Gun Company, he was attached to the 16th (Irish) Division, which experienced some early success during the Battle of Guillemont—a hard-fought engagement amid the broader chaos of the Somme offensive.

September 1916 – Missing in Action

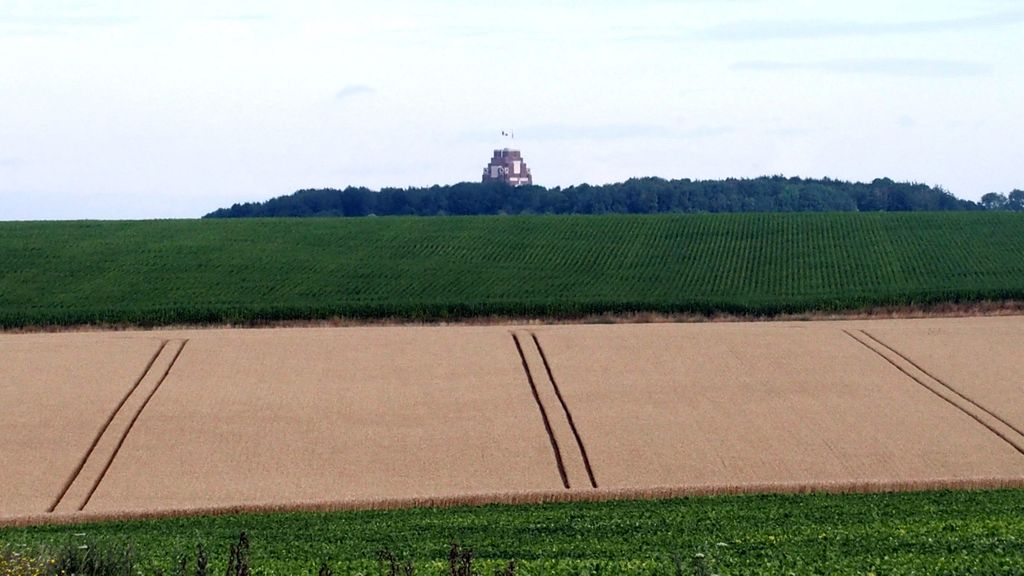

After just 297 days in uniform, George was reported missing in action following the fierce fighting at the Battle of Guillemont. He was later presumed killed, one of many young lives lost in the chaos of the Somme. His name is etched into the Thiepval Memorial, which honors more than 72,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers whose bodies were NEVER recovered from the battlefields of France and Flanders—a lasting tribute to those who vanished amid the mud and fire.

The Second Boer War

Albert Arthur Shurvinton33

Sapper

Royal Army 🇬🇧

Royal Engineers 17th Co. Natal Field Force

Died May 19, 1900

Estcourt, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

28 years old

1891 – A Pre-War Blacksmith

Albert, the eldest son of John,34 a gardener, and Amelia,35 a nurse, grew up alongside his younger brother Ernest36 and his older sister Beatrice.37 Like many of my Shervington cousins, the family made their home in Warwickshire, England. By 1891, Albert was 19 years old and had established himself as a blacksmith—a skilled trade that would shape the early years of his life before the shadow of war loomed over the British Empire.

1893–1896 – Albert Joins the Service

Still unmarried, Albert enlisted in the Royal Army, where he was assigned to care for the horses as a Sapper. He completed three years of active duty before volunteering for an additional three years in the reserves.

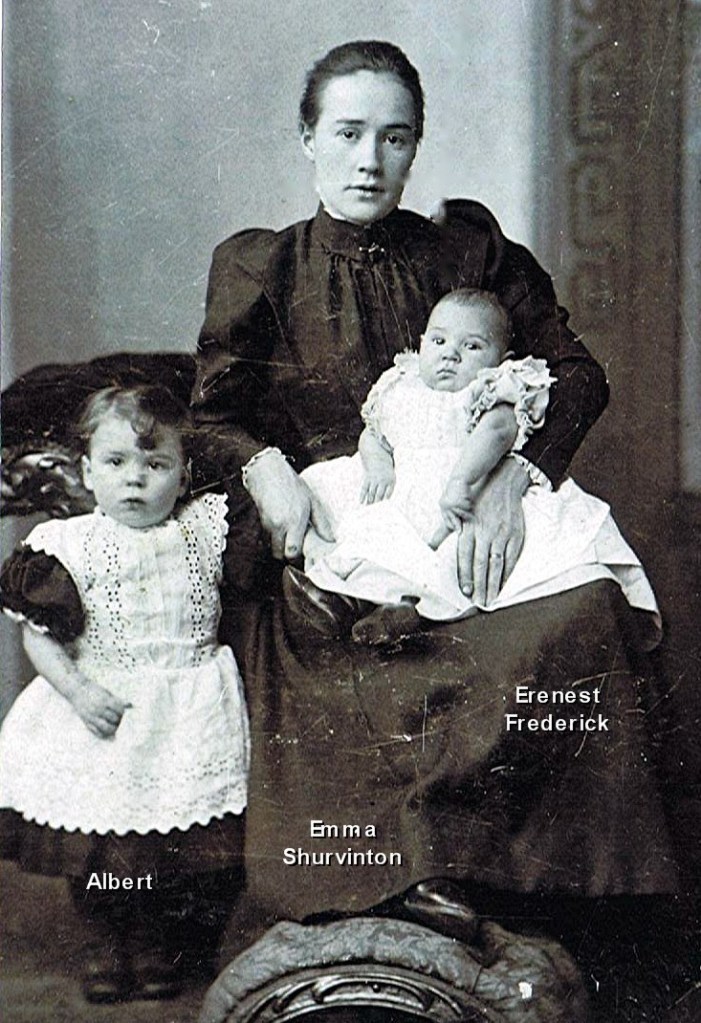

1897 – Albert Starts a Family

In 1897, Albert married Martha Emma Rogers,38 who preferred to go by her middle name, Emma. The following year, they welcomed their first son, Albert Victor,39 and in 1899, their second son, Frederick Ernest,40 was born.

Brothers

Albert and his younger brother, Ernest, shared a close bond. A reflection of their relationship can be seen in Albert giving his son Frederick the middle name “Ernest,” honoring his brother. Their connection was further evident when, in 1898, Ernest—already serving in the local militia—followed in Albert’s footsteps by joining the Royal Army. This deep bond would become even more apparent after Albert’s passing.

1899 – Albert is Recalled

Just three weeks after the birth of his son Frederick, Albert was called back from the reserves as negotiations between the United Kingdom and the two Boer republics in South Africa collapsed. The Second Boer War is about to begin.

1900 – Albert Fights Hard, but Loses

For seven months, Albert survived the perils of battle, enduring the fighting at Cape Colony, Tugela Heights, and the Relief of Ladysmith without injury. Yet, like so many of his comrades, he could not escape an enemy far smaller than a bullet—microscopic bacteria. Albert contracted enteric fever, a deadly illness that, during the Boer Wars, claimed more lives on both sides than combat itself. On May 19th, 1900, Albert died at Hospital No. 7 in Estcourt, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. His youngest son was not yet a year old.

A Brother Fights On

Albert’s younger brother, Ernest—still unmarried and serving with the 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards on the island of Gibraltar—was sent to South Africa just days after Albert. Their paths would soon cross on distant battlefields, far from the home they had known.

Despite the early loss of his brother during the conflict, Ernest pressed on, fighting through the brutal campaigns of the Second Boer War. He saw action at the Battle of Belmont, the Battle of Modder River, the Battle of Driefontein, and the Battle of Johannesburg. After more than two and a half years of service, Ernest finally returned home with the war’s end in June 1902.

A Brother Steps Up

Less than a year after returning home, Ernest—still unmarried—married his late brother Albert’s widow, Emma, and took on the role of father to Albert’s two young sons, Albert and Frederick. Together, Ernest and Emma would go on to build a new life, welcoming two more sons and two daughters into their growing family.

A Legacy of Service

Both of Albert’s sons, Albert Victor and Frederick Ernest, would go on to serve in the Royal Army during World War I. Unlike their father, they were fortunate enough to survive the war. Albert would no doubt have been proud to know that his brother, Ernest, helped guide his sons into responsible men who shared their father’s—and their uncle’s—deep commitment to serving their country.

The U.S. Civil War

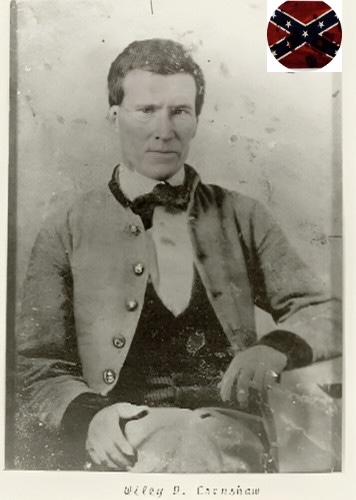

Wiley David Crenshaw41

2nd Sergeant

Confederate States Army

47th Alabama Infantry Regiment Co. F

Missing in Action May 6, 1864

Virginia

31 years old

Pre-Civil War Farming

Wiley was born in Georgia in 1833, and he’s the brother of my second great-grandfather, Joseph Madison Crenshaw.42 In search of cheap, fertile land for farming, this large Crenshaw family eventually moved westward to Alabama, settling in Tallapoosa.

1861 – Family and Farming Interrupted by War

In April 1861, as the Civil War erupted with the shelling of Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Wiley, his wife Martha,43 their five-year-old daughter Missouri Ann,44 and three-year-old son Francis Marion45 were tending their small family farm. By May 1862, when Confederate recruiters arrived at their property, Martha had just given birth to their third child, Emma Lucy.46 Wiley enlisted soon after, joining the 47th Alabama Infantry Regiment with the rank of Second Sergeant for a three year term.

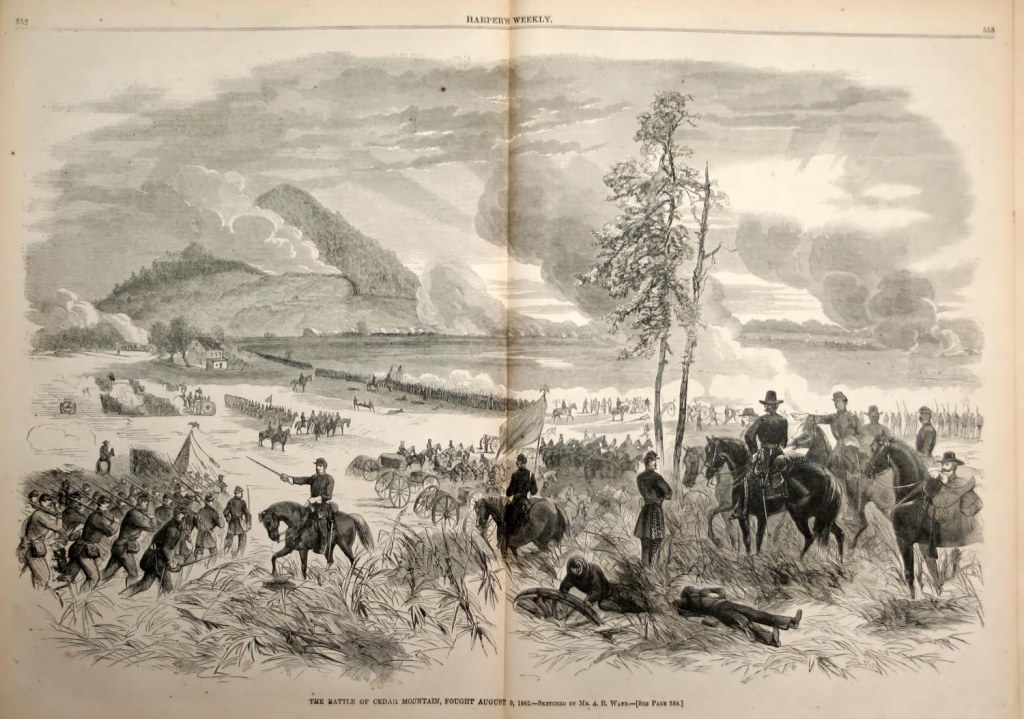

1862 – The Battle of Cedar Run

Wiley saw his first taste of battle just a few months later, after the 47th Alabama Infantry was incorporated into General Stonewall Jackson’s Army of Northern Virginia. At the Battle of Cedar Run, the Confederates outnumbered the Union forces by more than two to one. Wiley experienced victory in his first engagement and emerged from the fighting unscathed.

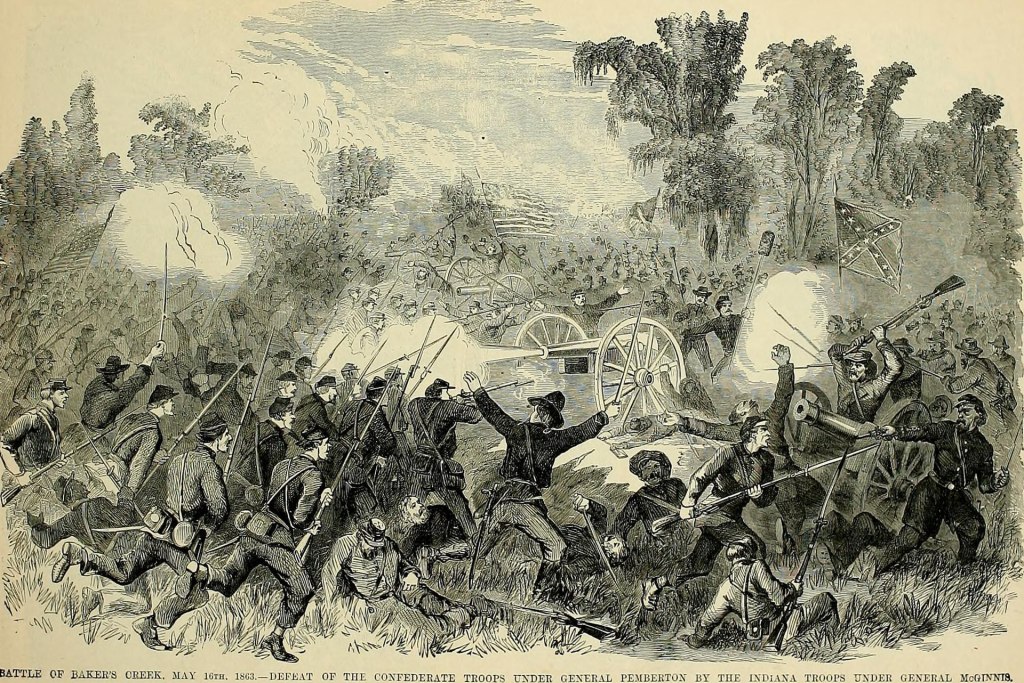

Months of Hospitalization

As disease and illness spread through the camps, Wiley was marked as “Absent/Sick” for nearly 11 months, keeping him from participating in key battles such as Bull Run, Chantilly, Harper’s Ferry, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga. During this same period, his brother—my 2nd great-grandfather—Joseph, was shot in the left shoulder and knee while serving as a private with the 31st Alabama Infantry at the Battle of Champion Hill in Mississippi. Two months later, during the fighting at Vicksburg, Joseph was captured and taken as a prisoner of war.

Return to the Fight

Wiley returned to active duty in October 1863, as his regiment helped defend the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee against the advancing Union Army. A month later, he took part in the Battle of Lookout Mountain, sparked by the Union’s attempt to break the Confederate siege. Although Wiley emerged unscathed, his unit suffered defeat, which led to another Confederate loss soon after at Missionary Ridge.

Fall Back and Second Victory

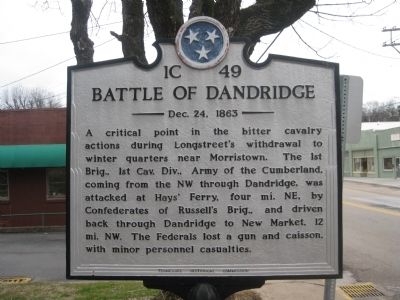

After the fall of Chattanooga, Wiley’s unit retreated to help defend Knoxville against the advancing Union forces. In early 1864, Wiley fought at the Battle of Dandridge, where the Confederates, seeking to regain the initiative, launched an attack against the Union Army of the Ohio. The Confederates succeeded in forcing a Union retreat, but a shortage of artillery ammunition and critical supplies prevented them from pursuing the fleeing forces and forced them to abandon their offensive.

Wiley’s Last Battle

By April 1864, Wiley’s unit, still part of the Army of Northern Virginia, had been reassigned to the Eastern Theater to defend Richmond. That spring, the Union’s new commanding general, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant,47 (my 7th cousin six times removed) launched the Overland Campaign, leading his forces across the Rapidan River east of Fredericksburg. Before Grant could mount a full assault, Confederate forces struck first, igniting the brutal Battle of the Wilderness on May 5, 1864. Over three days of savage and chaotic fighting, the Confederates suffered more than 17,000 casualties, while Union losses exceeded 11,000. With just one week left on his enlistment, Wiley was among the roughly 3,000 Confederate soldiers listed as missing or captured. His remains were never found or identified.

Horatio Gates Harlow48

Private

Union Army

58th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment Co. C

Died November 28, 1864

Virginia

31 years old

A Pre-Civil War Mariner

Horatio, my third great-granduncle, was born in 1829 in Wareham, Massachusetts. He was the brother of my third great-grandmother, Mary Elizabeth Harlow.49 The Harlow family descends from several passengers who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620. This branch of my family tree is a recent and exciting discovery, uncovered through my grandmother’s50 adoption records, which revealed the identity of her biological mother.51

February 1864 – Enlistment

At 34 and still unmarried, Horatio put his seafaring life on hold to enlist in the Union Army. His younger brothers, James52 and Lemuel,53 had entered the war three years earlier in 1861—James still serving with the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, while Lemuel had just completed his term with the 23rd the month before. Both had seen intense combat. Perhaps it was Horatio’s sense of duty as the protective older brother—and the relief of Lemuel’s safe return—that moved him to trade the sailor’s life for a soldier’s, and join the fight for the Union cause.

Brothers Reunited

Horatio joined the 58th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment and, after about two months of training, was deployed to Virginia in April 1864. There, his unit joined up with the 23rd Massachusetts—Lemuel’s old regiment—and the 20th Massachusetts, where James was still serving. For the first time since the war began, the two brothers stood together, reunited on the eve of battle, as General Grant47 prepared to lead the Union Army across the Rapidan River to launch the Overland Campaign.

Uncle vs. Uncle

On May 5, 1864, Confederate forces launched a surprise attack, catching Union troops off guard and igniting the fierce Battle of the Wilderness. Among the chaos, brothers Horatio and Samuel are now unknowingly pitted against my Confederate uncle, 2nd Sergeant Wiley D. Crenshaw41 with the 46th Alabama. When the fighting ceased two days later, Horatio, Lemuel, and James had escaped injury. Sergeant Crenshaw was declared missing in action.

Wounded

After surviving the brutal fighting in the Wilderness battle, Horatio went on to fight in the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House and the skirmish at the Ny River. On May 15, 1864—just ten days into his first combat experience—Horatio was wounded during the assault on the infamous Muleshoe Salient at Spotsylvania. Though listed as a casualty, the extent of his injuries remains unclear. What is known is that his wounds were not severe enough to remove him from the front lines. Instead, Horatio remained with his regiment as they pressed forward in pursuit of General Lee’s54 forces toward Petersburg.

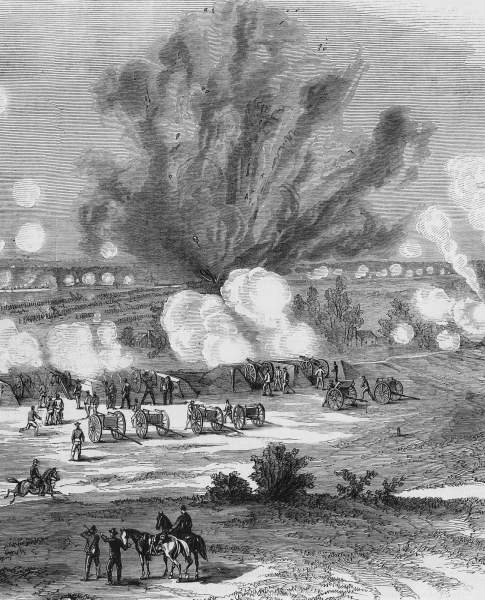

Explosion, Chaos, Captured

The Siege of Petersburg had begun, and with it, one of the most dramatic moments of the campaign. Union forces constructed a mine shaft beneath a section of the Confederate salient and packed it with explosives, hoping the blast would create a breach wide enough for their troops to pour through. On June 30th, the mine was detonated, unleashing a massive explosion that stunned even the Union attackers and threw the battlefield into chaos. The assault that followed quickly unraveled, and the hoped-for breakthrough collapsed into confusion and heavy casualties on both sides. Amid the disorder, many soldiers were captured by the enemy—including Horatio, who now found himself a prisoner of war.

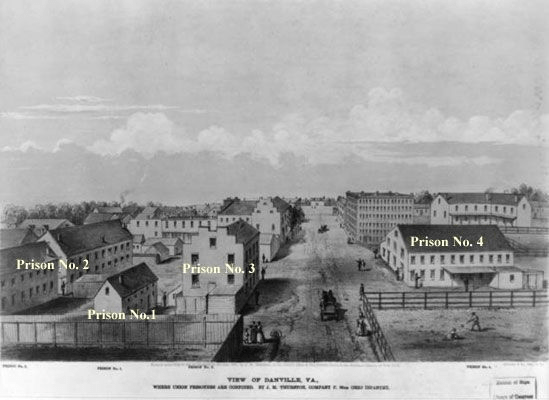

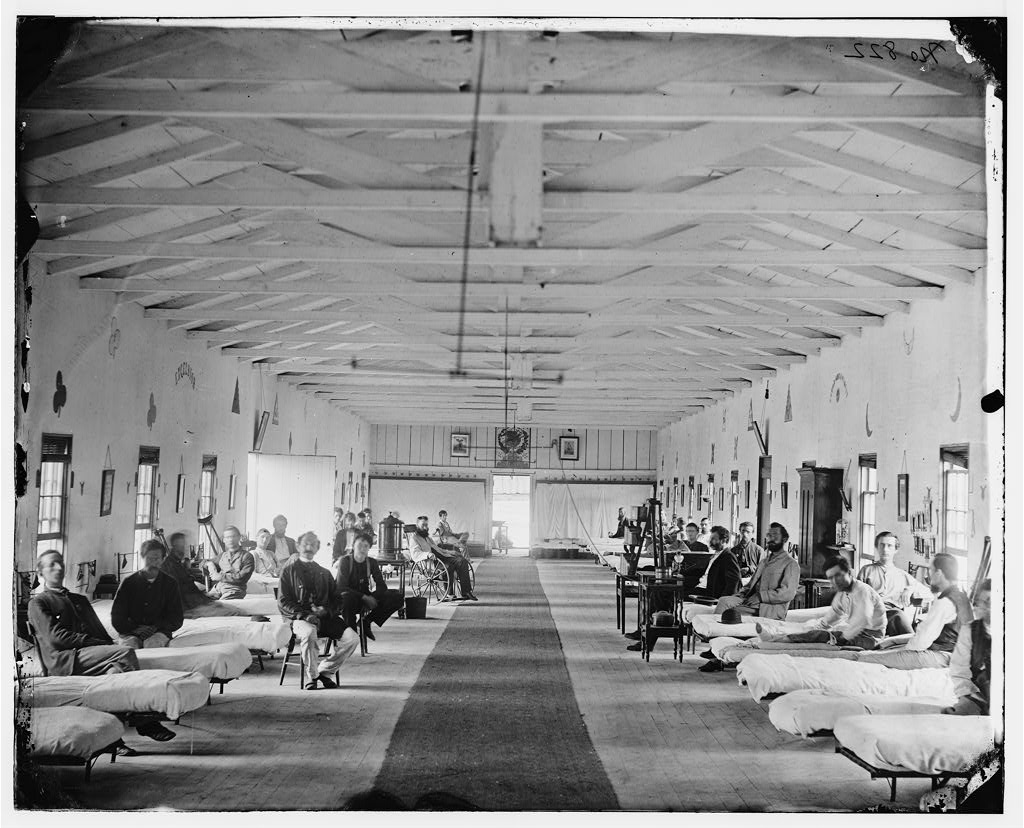

Prisoner of War

Just four months after enlisting, Horatio had already endured the horrors of battle, suffered wounds, and now faced the grim reality of life as a prisoner of war. He was confined in Danville, Virginia, where six abandoned tobacco warehouses had been hastily converted into prison camps far from the front lines. Conditions were dire—overcrowded, unsanitary, and poorly supplied—leading to widespread disease and death among the imprisoned.

The Fever and Death

After five harsh months in captivity, Horatio’s health deteriorated to the point that he was transferred to the local hospital in Danville. In most cases, such transfers were less about providing genuine care and more about removing the dying from within the prison walls. On November 30, 1864, Horatio succumbed to endemic fever and was buried in a cemetery near the hospital. He died never knowing that his brother, Lemuel, would survive the war and stand at Appomattox as the Confederacy surrendered, bringing the long conflict to an end.

David C. Bumpus56

Private

Union Army

24th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment Co. B

Died September 30, 1864

New Bern, N.C.

31 years old

Colonial Lineage

David and I both descend from my 6th great-grandfather, Joseph Bumpus,57 who was born in 1729 in Wareham, colonial Massachusetts. While Joseph is our closest common ancestor, we also share a deeper lineage through his great-grandfather, Edward Bumpass,58 who arrived in the American colonies from London aboard the Fortune in 1621. The Fortune was the first ship to arrive in Plymouth after the Mayflower.

A Pre-War Seaman and Young Father

David was the youngest of four brothers59 60 61and a seaman by trade, which was a common profession in the area around Boston Harbor. In the Spring of 1858, he was 25 years old and had already lost both his parents.62 63 However, in the Summer of that same year, he married Maria Ellen Perry64 and started a family of his own. Unfortunately, their first child, Henry,65 died at just over a year old.

The War Between the States and a Second Child

The Civil War broke out in April 1861, just two months following the death of David’s infant son. David’s wife, Maria, was pregnant for the second time and expecting to deliver in October. David enlisted in the 24th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment on September 25, 1861, and left for training on October 2. Maria gave birth to Abigail66 just six days later.

Brothers Unite

Though David was the youngest of his brothers, he was the first to enlist in the service of his country. Within a month of his volunteering, his three older brothers—Benjamin,59 Henry,61 and Lysander “Noble”60—also answered the call to arms. Remarkably, all four brothers would go on to serve together in Company B of the 24th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.

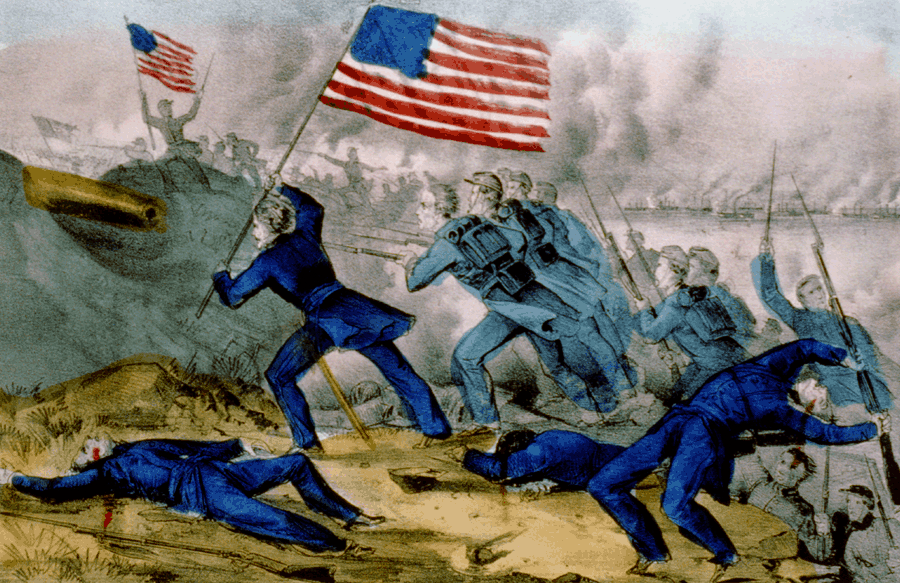

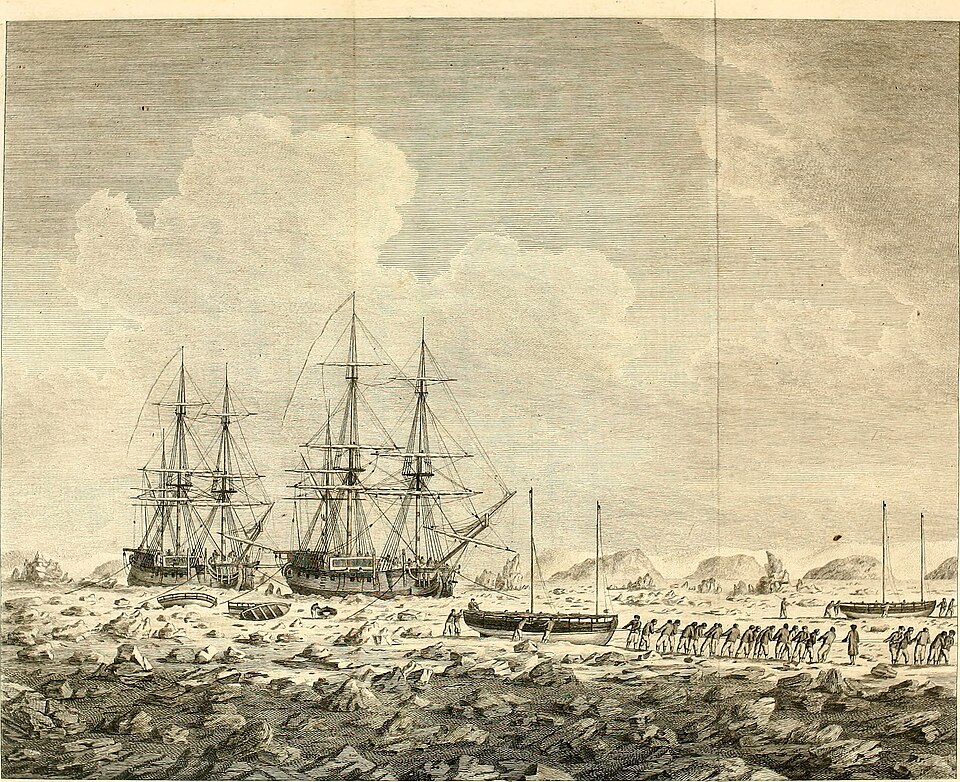

The First Battle

General Burnside67 led a 7,500-strong Union force southward, tasked with seizing control of key coastal regions in Virginia and the Carolinas—critical supply routes for whichever side could hold them. In February 1862, the 24th Massachusetts Infantry landed on Roanoke Island, where they faced a Confederate force roughly half their size. Backed by Union naval gunships, the superior numbers and firepower quickly overwhelmed the defenders. With over 80% of the Confederate force neutralized, they surrendered. The 24th suffered relatively light losses, with around 260 men killed or wounded.

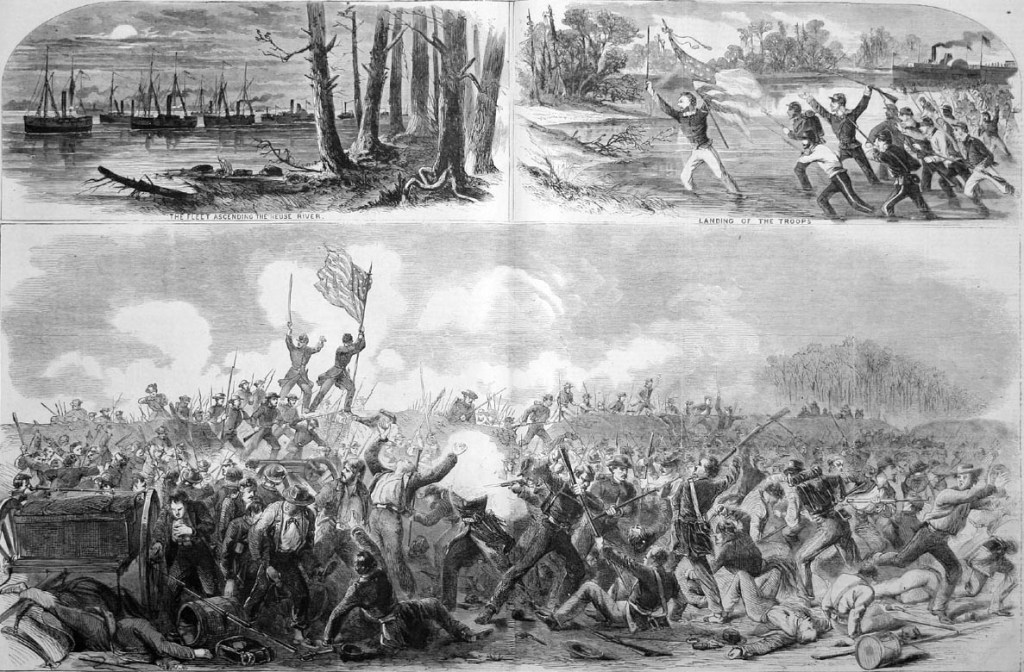

The Battle of New Bern

Fresh off their success at Roanoke Island, Union forces quickly turned their attention to the strategic city of New Bern, North Carolina. On March 14, 1862, the battle began, and after four hours of intense combat, Union troops secured a decisive victory. The fighting resulted in over 1,000 combined casualties on both sides.

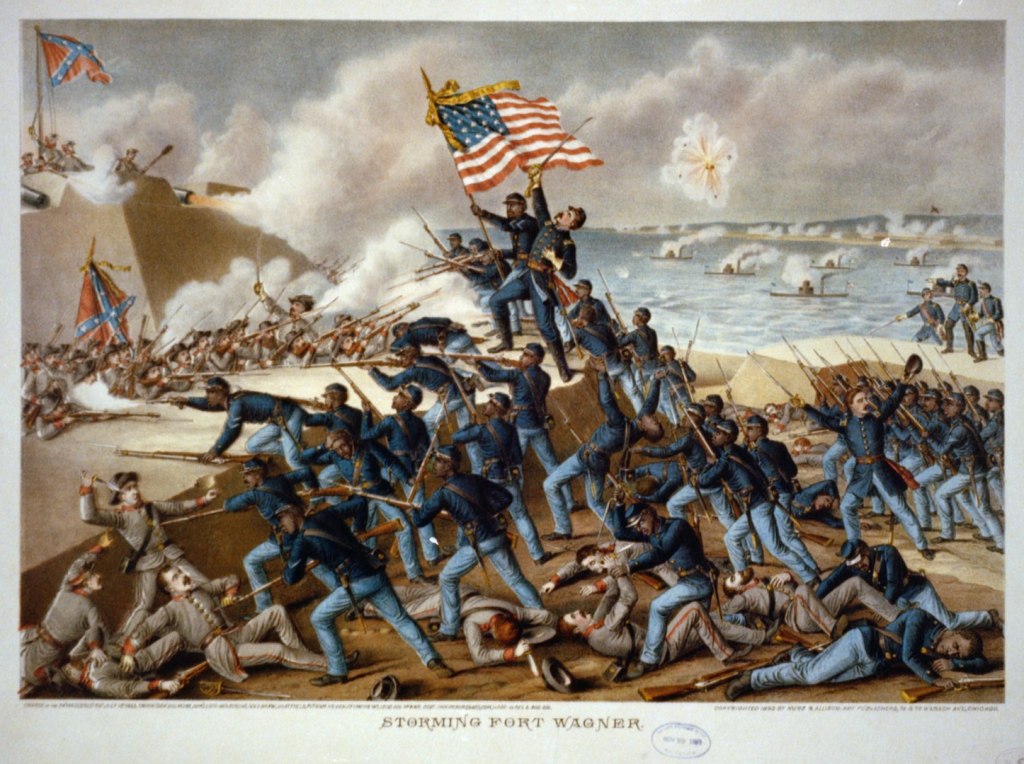

The Battles for Fort Wagner

As portrayed in the film Glory, the 24th Massachusetts played a role in the assaults and subsequent siege of Fort Wagner during the summer of 1863. The second major Union assault was led by the all-Black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, commanded by my 7th cousin four times removed, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.68 Though the attack did not succeed in capturing the fort, the extraordinary courage shown by the men of the 54th shattered doubts about the capabilities of Black soldiers and proved they were equal to any in battle—if only given the chance.

A Brother Falls

Over the previous 18 months, the four brothers had taken part in expeditions, reconnaissance missions, and numerous battles and skirmishes across the barrier islands stretching from Virginia to South Carolina. By the fall of 1863, the 24th Massachusetts was headquartered on James Island, South Carolina—but David had fallen seriously ill. He was transferred to Foster General Hospital in New Bern, North Carolina—the very city he had helped seize from Confederate control. Now, that city was tasked with saving his life. Tragically, David succumbed to yellow fever on September 30, 1863. He died without ever meeting his only child, Abigail.

Three Brothers Fight On

After David’s death, his brother Benjamin was captured by Confederate forces but was later exchanged in March 1865. Promoted to the rank of corporal, Benjamin served with the Union occupation forces in Richmond, Virginia, until he was mustered out in January 1866.

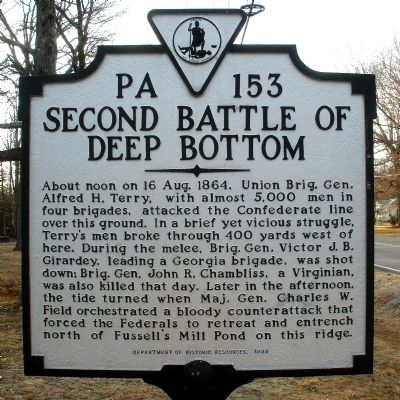

Meanwhile, in August 1864, brothers Henry and Noble fought side by side during the brutal Second Battle of Deep Bottom, part of the Petersburg–Richmond Campaign. Both were wounded in the fighting. The Union suffered heavy losses in the battle, with approximately 2,900 casualties—more than twice the number sustained by Confederate forces. Despite their injuries, both brothers survived and were later reunited with Benjamin during the occupation of Richmond.

Benjamin Franklin Bumpus69

Private

Union Army

20th Massachusetts Infantry Co. A

Died January 16, 1863

Lookout Point, MD

36 years old

Colonial Lineage

Like David C. Bumpus,56 Benjamin and I trace our ancestry back to my 6th great-grandfather, Joseph Bumpus,57 who was born in Wareham, Massachusetts, in 1729. Many members of our extended family—grandfathers, uncles, and cousins—served during the American Revolution, contributing to the fight for independence.

An Only Son and Father

Benjamin was the only son of Barzillai70 and Theodate,71 growing up with three sisters.72 73 74 In 1847, at the age of 20, he married Elizabeth75 and was working as a laborer. Together, they had four children76 77 78 79, though tragically, two or three died young or at birth.

War Breaks Out

In April 1861, the Civil War erupts. Far from the battlefields, in Massachusetts, Benjamin is working as an iron worker while Elizabeth is pregnant. That September, she gives birth to their only son, Benjamin Burgess Bumpus79—but heartbreak follows, as the child dies just four days later. One year later, Benjamin enlists.

20th Massachusetts

Like James Harlow52 mentioned earlier, Benjamin enlisted in the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. This regiment, often called the “Harvard Regiment,” earned its nickname due to the high number of officers—and even some enlisted men—who were Harvard College alumni. By the time Benjamin joined, the 20th had already experienced heavy combat, including notable engagements at the Battle of Bull Run, Siege of Yorktown, and the bloody contest at Antietam.

Catching Up with the Regiment

Along with a group of new replacements, Benjamin joins the 20th Massachusetts shortly after their brutal engagement at Antietam. The regiment has moved to Harper’s Ferry for a period of replenishment, guard duty, reconnaissance, and security patrols.

On the Move

Just three weeks after the bloodshed at Antietam, Benjamin and his fellow soldiers receive orders to march up the Loudoun Valley toward Falmouth, Virginia. There, they are to prepare for an assault on the heavily fortified city of Fredericksburg.

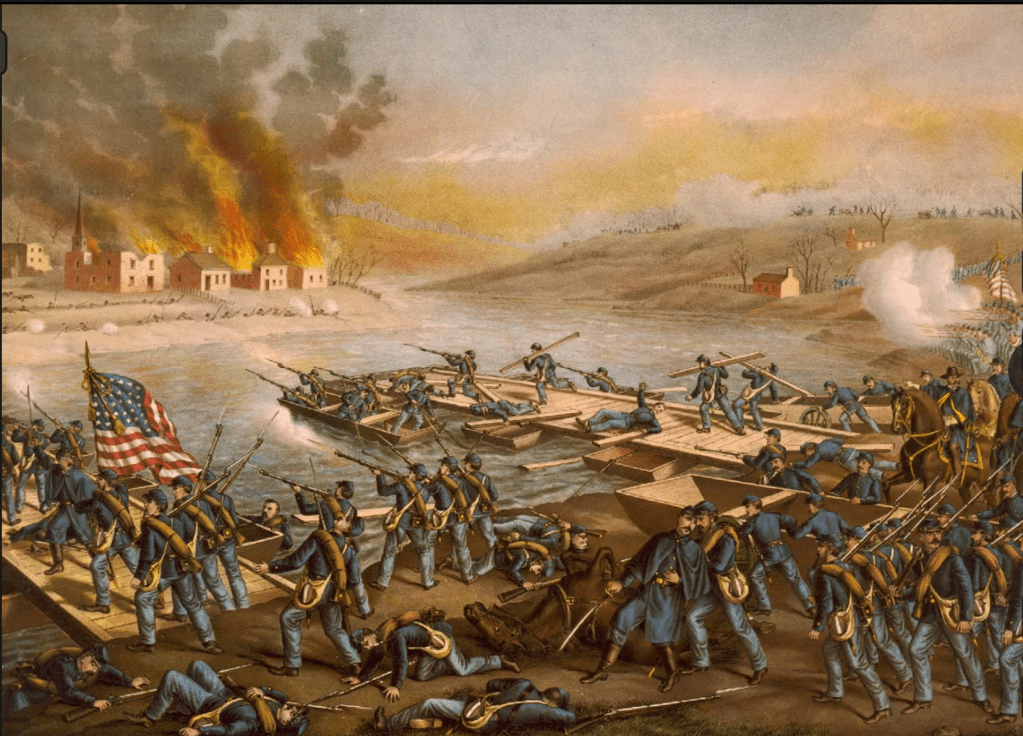

The Battle of Fredericksburg

The battle begins on December 11, 1862, when Union General Ambrose Burnside67 orders the construction and crossing of five pontoon bridges over the Rappahannock River. As Union troops attempt to cross, they come under immediate and intense fire from well-entrenched Confederate forces on the Fredericksburg side. During this initial advance, Benjamin is severely wounded.

Medical Evacuation and Death

After five days of fierce combat and actually taking control of the city, the Union army is forced to retreat back across the river, having suffered approximately 12,600 casualties—nearly double that of the Confederate forces. Benjamin, along with other gravely wounded soldiers, is eventually evacuated to Hammond Federal Hospital at Point Lookout, Maryland. He dies from his wounds about five weeks later.

Jonathan R. Nye V.80

Private

Union Army

1st Rhode Island Light Artillery Regiment, Battery F

Died August 3, 1862

New Bern, N.C.

16 years old

A 1635 Grandfather – Just like my cousin David Nye11 mentioned earlier, Jonathan and I descend from Benjamin Nye15 of London England who arrived in the colonies sometime before 1635.

A Teenager

Jonathan was born on his family’s farm in Westerly, Rhode Island, the youngest of six children. He had two older brothers and three older sisters. In 1855, when Jonathan was just 9 years old, his sister Susan died at the age of 14—a loss that marked his early childhood.

Too Young to Fight?

Although the Union Army officially required enlistees to be at least 18 years old, many underage boys still managed to join the ranks. It’s estimated that about 10% of Union soldiers were under 18, often by lying about their age or having it overlooked by recruiters eager to fill quotas. In contrast, the Confederate Army had no formal age requirement, and as many as 20% of its soldiers were underage—reflecting how both sides, desperate for manpower, frequently ignored age restrictions.

According to official Union Army records, Jonathan was listed as 18 at the time of his enlistment. However, U.S. Census data confirms he was actually only 16.

Two Brothers Join

On March 19, 1862, 16-year-old Jonathan enlisted in Battery F of the 1st Rhode Island Light Infantry Regiment. Just ten days later, his older brother Henry enlisted in the same unit—perhaps driven by a sense of duty, or a desire to watch over his younger brother on the battlefield.

Ordered to New Bern, N.C.

By the time Jonathan and Henry enlisted, Battery F had already been active for five months, carrying out assignments in Annapolis, Washington, D.C., and parts of Virginia. The brothers were part of a fresh wave of reinforcements—new troops and supplies—sent to join the battery stationed near the recently captured town of New Bern, North Carolina.

Sickness Takes a Teenager

While stationed in New Bern, Battery F was tasked with rear-area security, conducting patrols and launching raids on known Confederate positions. These missions occasionally led to dangerous encounters with enemy patrols, resulting in skirmishes that brought injuries, captures, and even death.

By late July 1862, Jonathan had fallen seriously ill and was admitted to the New Bern General Hospital. Despite efforts to treat him, he died on August 3rd at just 16 years old. Following his brother’s death, Henry was granted a brief furlough to grieve. He soon returned to duty, was wounded at some point in service, reenlisted, and ultimately mustered out in 1866 during the Union occupation of Richmond, VA.

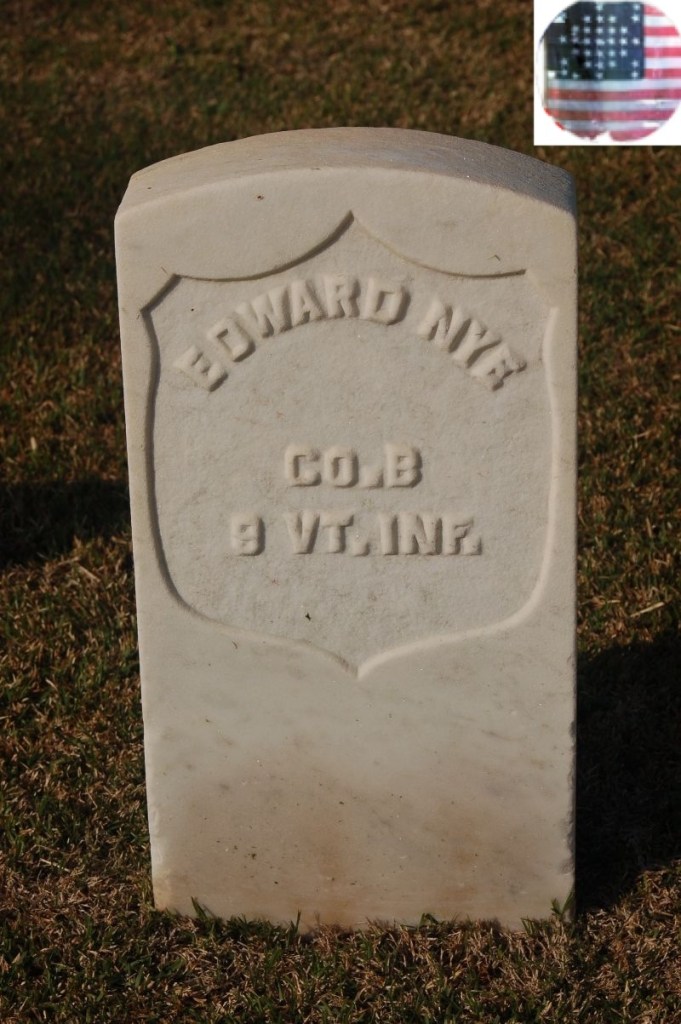

Edward Nye

Private

Union Army

3rd Vermont Volunteer Infantry Co. B

Died June 22, 1864

Washington D.C.

21 years old

Another Nye Cousin

Edward Nye of Irasburg, was the youngest of four siblings, born around 1843 in the green hills of Vermont. As the baby of the family, he likely grew up in the shadow of his older brothers, especially Lucius, with whom he would later share a harrowing chapter of American history.

Military Enlistment

Though records of Edward’s service are limited, it’s believed he enlisted in the Union Army alongside his older brother Lucius. In February 1863, Edward was 21 and Lucius was 23. It had been seven months since the formation of the 3rd Vermont Volunteer Infantry, and the two unmarried brothers joined Company B, ready to serve a cause that had already demanded much from their state and their fellow Vermonters.

Battles and Wounds

By the time Edward and Lucius reached their unit, the regiment was already embroiled in the Peninsula Campaign and fierce fighting at Yorktown and Williamsburg. Over the next two years, the brothers fought side by side in several key battles, including Fredericksburg and the pivotal clash at Gettysburg. Lucius distinguished himself in combat and was promoted to Corporal. But the war soon took its toll—on May 5, 1864, during the brutal Battle of the Wilderness, Lucius was wounded in what would become part of General Grant’s relentless Overland Campaign.

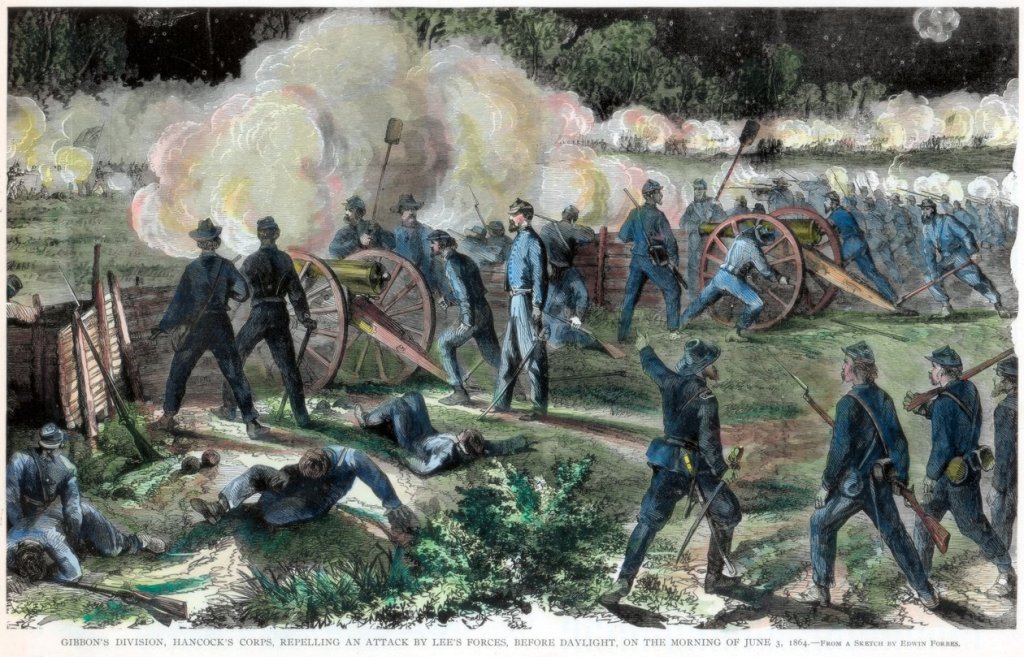

The Battle of Cold Harbor

Just a month later, Edward and Lucius found themselves entrenched on the front lines at Cold Harbor. Nearly 110,000 Union troops were positioned across a seven-mile front, facing a Confederate force of about 60,000. On command, the Union army launched an assault—one that would end in devastating loss. The Confederates held their ground, and the Union suffered roughly 18,000 casualties compared to 5,000 on the Confederate side.

Among the wounded was Edward, struck by a gunshot during the assault. He was initially treated at a field medical station near the battlefield, but due to the severity of his injury, he was transferred over 100 miles north to Armory Square Hospital in Washington, D.C. There, in one of the largest and most advanced military hospitals of the time, Edward joined thousands of other wounded soldiers recovering from the horrors of Cold Harbor—a place where the cost of war had become tragically clear. Unfortunately, Edward would die of his wounds a few weeks after his arrival.

Lucius Fights On

Edward’s brother, Lucius, remained with the 3rd Vermont and continued to fight bravely after Edward’s death. Just three months later, he was wounded for a second time—this time during the Battle of Opequon (also known as the Third Battle of Winchester), one of the major engagements of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

Lucius survived the war and returned home. In time, he married Abbie Ross, and together they had two sons. But their happiness was short-lived. Abbie died suddenly at the age of 26, just three and a half years into their marriage, leaving Lucius a young widower and father.

Edward Nye

Private

Union Army

9th Vermont Infantry Co. B

Died March 30, 1864

New Bern, N.C.

25 years old

A Fourth Cousin

Edward Nye of Pawlet, Vermont, was a fourth cousin to the Edward Nye of Irasburg whose story was told earlier. Close in age, the two Edwards lived lives shaped by different circumstances, separated by about 150 miles of Vermont’s green hills.

A Pauper’s Start

In the 1860 census, 21-year-old Edward was living with his grandparents and listed as a pauper. He appeared to be an only child, estranged from his father—an unmarried man living with his single sister. Edward’s mother remains unknown, and little else is recorded about his early life, except for the fact that he began adulthood with few resources and limited family support.

The 9th Vermont Infantry

The 9th Vermont was originally mustered in July 1862 and soon found itself in action. However, their early combat experience came to a halt with their surrender at the Battle of Harpers Ferry in September of that year. After being paroled, the regiment was reassigned to guard duty, overseeing Confederate prisoners in Chicago, Illinois. In January 1863, the unit was officially exchanged and then moved to Virginia, where they continued their role guarding prisoners of war.

Drafted into Service

In August 1863, Edward was among 164 men drafted to replenish the 9th Vermont. Mustered at Brattleboro, he was initially marked as a deserter on August 28th. It’s unclear whether he was late to report, had second thoughts, or was later found and persuaded—perhaps forcibly—to return. Regardless, he ultimately rejoined the unit before it shipped out to Virginia.

Deployment to North Carolina

That fall, the 9th Vermont was ordered south to defend the strategic port town of New Bern, North Carolina, which Confederate forces repeatedly attempted to reclaim. Edward joined the regiment there in October 1863, as the unit shifted roles between rear-area security and protecting transportation routes through Virginia, Maryland, West Virginia, and the Carolinas.

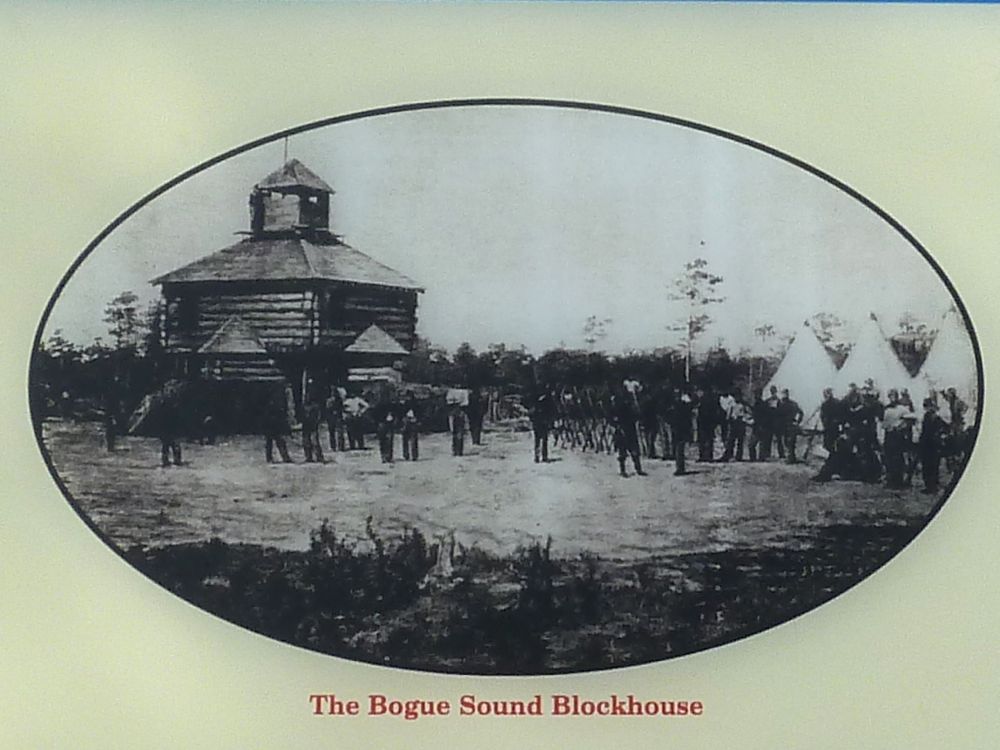

The Bogue Sound Blockhouse

In February 1864, Edward’s Company B—alongside Company H—was assigned to guard the crossroads of Bogue Sound Road and Newport Road in Carteret County, North Carolina. When Confederate forces launched another offensive aimed at retaking New Bern, they encountered Edward’s position. The Confederates overran the outpost, captured the blockhouse, and set it ablaze. Many of the inexperienced Union defenders, including Edward’s company, were forced to retreat under pressure.

Illness and Death

Not long after the engagement at Bogue Sound, Edward fell ill. He was transported to the General Hospital in New Bern for treatment, but despite medical care, his condition worsened. He died of disease and was laid to rest in the hospital cemetery, alongside many others who succumbed not only to bullets, but to the silent ravages of illness.

Though the 9th Vermont saw comparatively little combat, it suffered heavily from disease—by war’s end, only 24 men had been killed or mortally wounded in battle, but 278 had died from sickness. Edward Nye was among them, one of countless soldiers whose sacrifice came not in glory, but in quiet endurance.

American Revolutionary Way

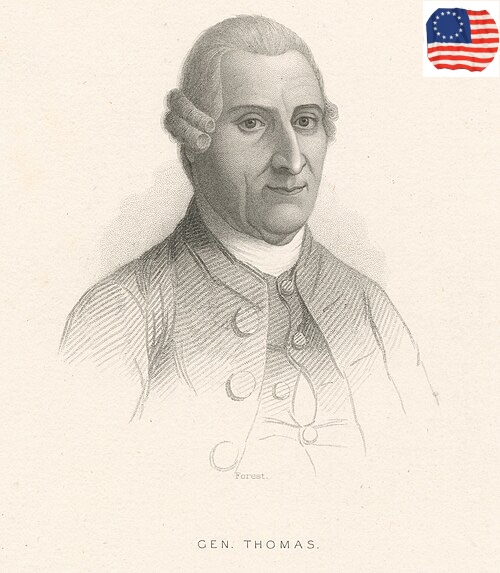

John Thomas

Major General

Continental Army

2nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

Died June 7, 1776

Quebec, British America

51 years old

A Third Cousin

General Thomas was my third cousin, eight times removed. We both descend from my 11th great-grandfather Thomas Bourne, who immigrated from England around 1637.

A Doctor and Military Surgeon

Thomas was a practicing physician with his own medical practice in Kingston, Massachusetts. At the age of 22, he was appointed surgeon to a British Colonial regiment during King George’s War, which led him north into Nova Scotia. He found military life fulfilling and eventually took on a leadership role, serving as a lieutenant.

Rising Through the Ranks

By 1759, Thomas had risen to the rank of colonel and was actively serving in the French and Indian War. He returned to the northern territories, this time commanding the lead division during the Montreal Campaign.

The War of Independence

In 1775, following his leadership during the Siege of Boston, Congress appointed Thomas as a Brigadier General and gave him command of the troops he had raised as a colonel. In March 1776, he fortified Dorchester Heights, recognizing its strategic advantage over the City of Boston. Leveraging this position, he successfully forced the British to evacuate the city. His decisive action earned him a promotion to Major General.

Change of Command

While General Thomas was engaged in battle against the British around Boston, another cousin of mine, General Richard Montgomery, was fighting in the Battle of Quebec. Tragically, Montgomery was killed while leading a charge on a palisade. In May 1776, General Thomas was ordered to take command of the remaining forces, who had been left leaderless and struggling in the aftermath.

Tattered and Diseased

When General Thomas arrived in Quebec, he found the remnants of General Montgomery’s forces exhausted, demoralized, and ravaged by a smallpox epidemic. Acting swiftly, he ordered a retreat to allow the troops to receive medical care and much-needed supplies. Tragically, Thomas soon contracted smallpox himself and died shortly thereafter.

Nathaniel Woodhull

Brigadier General

Continental Army

New York Militia

Killed in Action September 20, 1776

New Utrecht, New York

53 years old

A Third Cousin

General Woodhull was my third cousin, ten times removed. We both trace our ancestry to my 12th great-grandmother, Elizabeth Hammond (nèe Paine), who arrived in the American colonies in 1634 aboard the Francis with her two young sons.

Colonial Militia

In 1758, at the age of 36, Nathaniel joined the New York militia and was commissioned as a Major. Serving under British command, Major Woodhull took part in the Battle of Fort Frontenac during the Seven Years’ War and fought in the 1758 Battle of Ticonderoga during the French and Indian War.

The War of Independence

In 1775, Nathaniel was appointed Brigadier General of the Suffolk and Queen’s County militia. During the Battle of Long Island in 1776, he was captured by British forces under the command of Captain Sir James Baird of Fraser’s Highlanders.

Capture and Death

After his capture, Nathaniel was struck multiple times with a sword for refusing to say, “God save the King.” Instead, he responded, “God save us all.” He was then imprisoned in the brig of a ship, where his untreated wounds became infected. Eventually moved to a house on land, he succumbed to his injuries and died shortly thereafter.

Nicholas Biddle

Captain

Continental Navy

USS Randolph

Killed in Action March 37, 1778

Lost at Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Near Barbados

27 years old

A Fourth Cousin

Captain Nicholas Biddle was my fourth cousin, ten times removed. Born in Philadelphia in 1750, he began his life at sea at just 13 years old, serving as a ship’s boy on a merchant vessel trading goods in the West Indies.

Royal Navy and Explorer

After seven years at sea, Nicholas Biddle joined the British Royal Navy as a midshipman at the age of 20. Three years later, he seized the opportunity to take part in the Phipps Expedition to the Arctic Sea. During this voyage, he served alongside a young Horatio Nelson, who would later become Admiral of the British Fleet.

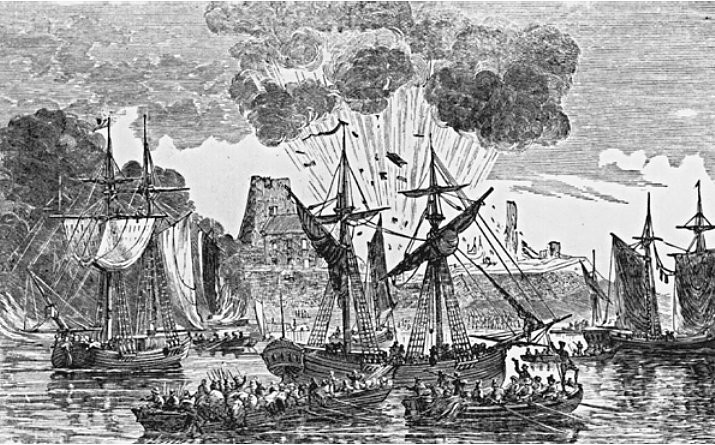

Joining the Fight for Independence

In 1775, Nicholas Biddle, now a captain, was given command of the armed galley USS Franklin, followed by the larger USS Andrew Doria, a 14-gun brig. Aboard the Andrew Doria, he took part in the Raid of Nassau on April 6, 1776—the first amphibious operation and marine assault conducted by our newly declared independent nation.

USS Randolph

Captain Biddle’s impressive record in combat and his talent for seizing enemy ships led to his appointment in June 1776 as commander of the newly commissioned 32-gun frigate USS Randolph. Under his leadership, the Randolph saw continued success—most notably with the capture of HMS True Briton along with the three ships sailing in her convoy.

Outgunned

In March 1778, while escorting a convoy of merchant ships off the coast of Barbados, Captain Biddle encountered the British 64-gun warship HMS Yarmouth poised for attack. Despite being heavily outgunned, he ordered his smaller escort vessel to join him in intercepting the much larger adversary, determined to protect the convoy. A fierce naval battle followed. Although the Randolph inflicted damage on the Yarmouth and successfully enabled the merchant ships to escape, a well-aimed shot struck her magazine, causing a massive explosion that sank the ship. Only four men survived—Captain Biddle was not among them, going down with his command.

Asa Pollard

Private

Continental Army

Massachusetts Militia

Killed in Action June 15, 1775

Massachusetts

39 years old

A Fifth Cousin

Asa Pollard was my fifth cousin, eight times removed. We both descend from my 12th great-grandfather, John Howse of Kent, England. Asa was born in 1735 on a farm in North Billerica, Massachusetts.

Colonial Militia

Asa served in the British colonial militia and saw action during the French and Indian War. With the onset of the American fight for independence, he enlisted in the Continental Army as a private on May 8, 1775, at the age of 39. He immediately took part in the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

First Casualty of Bunker Hill

On June 15, 1775, Asa took part in the Battle of Bunker Hill, fighting on Breed’s Hill. During the conflict, he was struck and instantly killed by a cannonball fired from a British ship, becoming one of the battle’s first casualties. He was hastily buried on the hill and his remains were never located.

Also Killed at Bunker Hill – Major General Joseph Warren, my 18th cousin eight times removed, was also killed during the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Thomas Knowlton

Lieutenant Colonel

Continental Army

Connecticut Militia Knowlton’s Rangers

Killed in Action September 16, 1776

New York

35 years old

A Sixth Cousin

Colonel Thomas Knowlton was my sixth cousin, eight times removed. We both descend from my 13th great-grandmother, Alice Perkins (née Kebble) of Warwickshire, England.

Early Life and Military Service

Thomas Knowlton joined the French and Indian War at fifteen, serving alongside his brother Daniel in scouting missions and later with Captain John Slapp’s company. Over six campaigns, he rose to the rank of lieutenant and also fought in Israel Putnam’s company during the 1762 British expedition to Cuba. By August 1762, Knowlton had returned home, married Anna Keyes, and eventually fathered nine children. At thirty-three, he was appointed a Selectman of Ashford.

America’s First Intelligence Unit

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knowlton is regarded as America’s first intelligence professional. His unit, Knowlton’s Rangers, conducted reconnaissance and gathered intelligence in the early Revolutionary War. Notably, Captain Nathan Hale served under his command.

Success at the Battle of Bunker Hill

Knowlton was ordered to Charlestown to support Colonel William Prescott. He led a 200-man work party that reinforced the defenses on Breed’s Hill, using dismantled fencing and fresh-cut grass to build a makeshift breastwork. Positioned to oppose the advancing British grenadiers, his men held their ground until the general retreat, providing cover for withdrawing troops. Remarkably, only three of Knowlton’s men were killed in the battle.

Fallen at Harlem Heights

On September 16, 1776, Knowlton led a scouting party ahead of Washington’s army at the Battle of Harlem Heights. After engaging British light infantry, his unit retreated and later joined a counterattack alongside Major Andrew Leitch’s riflemen. Ordered to strike the enemy’s rear, they mistakenly hit the right flank, losing the element of surprise. Under heavy fire, Knowlton pressed the attack but was mortally wounded, as was Leitch. Washington mourned his loss, calling him “the gallant and brave Col. Knowlton … an honor to any country.”

INDEX

- John “Jack” Shervington (1918-1944), my 4th cousin once removed. Find A Grave ID: 56547395; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Lily Florence (Brant) Shervington (1916-1975), wife of Jack Shervington. Finda A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Francis George Brant (1889-1918), father of Lily. Find A Grave ID: 13287681; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Alfred Shervington Jr. (1914-1971), Jack’s brother. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Frederick Shervington (1921-1999), Jack’s brother. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- James Ralph Guinn (1916-1944), my 3rd cousin twice removed. Find A Grave ID: 119859453; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Ernest Walter Pimm (1913-1941), my 4th cousin once removed. Find A Grave ID: 59984998; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Walter Pimm (1883-1934), father of Ernest. Find A Grave ID: 242846691; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Beatrice Ellen (Shervigton) Pimm (1884-1961), my 3rd cousin twice removed. (Find A Grave ID: 242846741; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Matome Ugaki (1890-1945), Rear Admiral, Japanese Imperial Navy. Find A Grave ID: 208833076; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- David Adams Nye (1921-1945), my 5th cousin thrice removed. Find A Grave ID: 56762532; Wikitree ID: ↩︎

- Frederick Isiaiah Nye (1892-1964), father of David. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Mary Eleanor (Smith) Nye (1896-1970), mother of David. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Adrienne (Nye) Waters (1924-2002), sister of David. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Benjamin Nye (1697-1790), my 7th great-grandfather, Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Alfred R. Tenny Jr. (1921-1944), Freind and fellow pilot of David Nye. Find A Grave ID; 56286099; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Charles Henry Shirvington (1897-1910), my 4th cousin once removed. Find A Grave ID: 56154753, Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- George Thomas Shirvington (1891-1933), brother of Charles. Find A Grave ID: 56154753; Wikitree ID; UTL ↩︎

- John Alfred Shirvington (1894-1924), brother of Charles. Find A Grave ID: 245727646; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- William Alfred Shirvington (1865-192), father of Charles. Find A Grave ID: 245682238; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Sarah Jane (Rowbotham) Shirvington (1865-1916), mother of Charles. Find A Grave ID: 233131938; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Edith Dora (Shirvington) Shaw (1895-1972), sister of Charles. Finda Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Thomas H. Shirvington (1896-1918), my 4th cousin once removed. Find A Grave ID: 56330789; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Eleanor Ellen (Moore) Shirvington (1872-1916), mother of Thomas. Find A Grave ID: 247566230; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- George Ernest Barber (1893-1916), my 1st cousin twice removed. Find A Grave ID: 12364446; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- George Samuel Barber (1871-1925), father of George. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Mary Elizabeth (Shervington) Barber (1865-1949), mother of George. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: ↩︎

- Lily Maud (Barber) Clarke (1892-1962), sister of George. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Gertrude Agnes (Barber) Steer (1895-1971), sister of George. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- May Maria Barber (1900-1918), sister of George. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Annie Victoria (Barber) Hollis (1901-1930), sister of George. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Doris Mary (Barber) Isaac (1904-1930), sister of George. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Albert Arthur Shurvinton (1872-1900), my 3rd cousin twice removed. Find A Grave ID: 223106934; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- John Shirvington (1837-1915), father of Albert. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Amelia (Edkins) Shirvington (1833-1916), mother of Albert. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Ernest Shurvinton (1874-1948), brother of Albert. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: ↩︎

- Beatrice Hannah Edkins (Shervington) Reeves (1863-1951), sister of Albert. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: ↩︎

- Martha Emma (Rogers) Shurvinton (1873-1944), wife of Albert and then wife of Albert’s brother, Ernest after Albert died in the Boer War. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Albert Victor Shurvinton (1898-1965), son of Albert. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID UTL ↩︎

- Frederick Ernest Shurvinton (1899-1970), son of Albert. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Wiley David Crenshaw (1833-1864), my 2nd great-granduncle. Find A Grave ID: 225307298; Wikitree ID: Crenshaw-1179 ↩︎

- Joseph Madison Crenshaw (1839-1925), my 2nd great-grandfather. Find A Grave ID: 277651691; Wikitree ID: Crenshaw-1622 ↩︎

- Marth Ellender (Messick) Crenshaw (1836-1910), wife of Wiley. (Find A Grave ID: 47998938; Wikitree ID: Messick-683 ↩︎

- Missouri Ann (Crenshaw) Wilson (1855-1935), daughter of Wiley. Find A Grave ID: 8231410; Wikitree ID: Crenshaw-1846 ↩︎

- Francis Marion Crenshaw (1858-1946), son of Wiley. Find A Grave ID: 47998555, Wikitree ID: Crenshaw-1847 ↩︎

- Emmaline Lucy (Crenshaw) Spivey (1861-1949), daughter of Wiley. Find A Grave ID: 47645153; Wikitree ID: Crenshaw-1848 ↩︎

- Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), my 7th cousin 6 times removed and Union Army General. Find A Grave ID: 411; Wikitree ID: Grant-468 ↩︎

- Horatio Gates Harlow (1829-1864), my 3rd great-granduncle. Find A Grave ID: 3267434; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Mary Elizabeth (Harolw) Bumpus (1836-1922), my 3rd great-grandmother. Find A Grave ID: 201421830; Wikitree ID: Harlow-3446 ↩︎

- Marjorie Arline (Graham) Shervington (1915-1980), my grandmother who was born, Florence Bradford Haskins. Find A Grave ID: 281162166; Wikitree ID: Haskins-2658 ↩︎

- Julia Ann (Haskins) Peelo (1894-1957), my great-grandmother. Find A Grave ID: 5936923; Wikitree ID: Haskins-2675 ↩︎

- James Allen Harlow (1842-1930), brother of Horatio. Find A Grave ID: 139576223; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Lemuel Samuel Harlow (1834-1865), brother of Horatio. Find A Grave ID: 139576235; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Robert Edward Lee (1807-1870), my 12th cousin seven times removed. Find A Grave ID: 615; Wikitree ID: Lee-3 ↩︎

- David Williams Harlow (1805-1857), my 4th great-grandfather and father of Horatio. Find A Grave ID: 139576187; Wikitree ID: Harlow-2556 ↩︎

- David C. Bumpus (1832-1863), my 2nd cousin five times removed. Find A Grave ID: 30433958; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Joseph Bumpus (1729-1778), my 6th great-grandfather. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Edward Bumpas (1605-1693), my 9th great-grandfather. Find A Grave ID: 34833800; Wikitree ID: Bumpas-130 ↩︎

- Benjamin C. Bumpus (1825-1890), brother of David. Find A Grave ID: 42243557; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Lysander Noble Bumpus (1827-1883), brother of David. Find A Grave ID: 114885469; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Henry Francis Bumpus (1833-1910), brother of David. Find A Grave ID: 42318292; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Benjamin B. Bumpus (1786-1858), father of David. Find A Grave ID: 42242433; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Zilpha Chubbuck Bumpus (1793-1853), mother of David. Find A Grave ID: 42242468; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Mary Ellen (Perry) Bumpus (1821-1915), wife of David. Find A Grave ID: 42338366; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Henry F. Bumpus (1859-186), infant son of David and Mary. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Abby Maria Ellen (Bumpus) Russell (1861-1950), daughter of David. Find A Grave ID: 197566734; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Ambrose Everett Burnside (1824-1881), Union Army General. Find A Grave ID: 3264; Wikitree ID: Burnside-329 ↩︎

- Robert Gould Shaw (1837-1863), my 7th cousin four times removed and Union Army Colonel. Find A Grave ID: 19467; Wikitree ID: Shaw-5134 ↩︎

- Benjamin Franklin Bumpus (1827-1863), my 2nd cousin five times removed. Find A Grave ID: 32550856; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Barzallai Bumpus (1785-1878), father of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Theodate (Cahoon) Bumpus (1796-1884), mother of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Nancy S. (Bumpus) Baker (1822-1908), sister of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: 136089566; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Betsey R. (Bumpus) Bumpus (1825-1890), sister of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: 144698570; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Data C. (Bumpus) Russell (1828d1902), sister of Benjamin, Find A Grave ID: 198929215; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Elizabeth (Bumpus) Baker (1823-1873), wife of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: 142115033; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Elizabeth Ann Bumpus (1851-____), daughter of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Abby T. Bumpus (1854-1854), daughter of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Elizabeth Franklin (Bumpus) Bumpus (1858-1900), daughter of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Benjamin Burgess Bumpus (1861-1861), son of Benjamin. Find A Grave ID: UTL; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎

- Jonathan Nye Jr. (1846-1862), my 5th cousin five time removed. Find A Grave ID: 3260361; Wikitree ID: UTL ↩︎